*

Niki and Yoko

From a Shitamachi Okami to a Niki de Saint Phalle Collector

*

*

Written by Yuki Kuroiwa

Translated by Nasuka Nakajima

*

Dedicated to Niki and Yoko

Dear Yoko,

Our meeting was a very special one. It was a meeting of destiny. We had no choice. We were meant to meet. I know that you feel that we knew each other in a former life and I also had a very strange feeling when I met you for the first time. I was excited and enthusiastic to meet you. I found it difficult to relate to your adoration of me and my work. It scared me and made me feel separated from you and isolated by the pedestal you had put me on. You had a special relation to my daughter Laura and I told her your adoration made me feel nervous.

Laura suggested I ask you to sing one of Peggy Lee’s songs for me next time I saw you. You did a brilliant imitation of her. It worked like a charm. I discovered another Yoko. You were a great performer and reminded me of Giulietta Masina.

Yoko, you told me one day you felt you were very mean to me in a former life. I always had the feeling that I was burnt unfairly as a witch in a former life and that this was the reason that I was given the privilege to be an artist who did unusual things. You told me that you felt you were the judge who sent me to be burned at the stake. That this was part of our Karma.

Whatever happened between us in a former life Yoko has been repaired. You have played a very important role in my life. Because of your belief in my work you created a whole museum for me and created a huge interest for my work in Japan. Never could I have dreamed as a young women that one day I would be known and loved in Japan. Did I live in Japan in a former life? Would that explain the strong calligraphic quality in my painting and drawings?

Yoko I love you, the way you dress, your elegance, your uniqueness. Your love for my work touches me today. I also appreciate that you have an excellent eye, rarely choosing the obvious pieces. Of course you like the Nanas as everyone does, but you also choose difficult pieces. You like my journey through art, my changes and developments. You did not get stuck in one period of my work. Yoko, you have collected a unique set of pieces, the largest in the world. You may be under my spell but I am also under yours.

I cannot say exactly what you represent for me because it remains shrouded in mystery, yet I feel you have an intuitive sense of me, as though we were blood sisters. It is a strange singular relationship. You are also a bit crazy like me.

Your husband made the museum in a traditional Japanese style which melds very well with the landscape. I was worried how my work would fit in. Even though this is an unexpected marriage it is one that works.

I like your courage and tenacity and your passionate soul. You are a unique extraordinary person who lives through your visions. Our strange story is not over yet. I feel there are many unexpected things to come.

Last night I had a dream. We were in our next life. You were a famous singer and I was your greatest fan! Yoko I salute you.

April 19, 1998 Niki de Saint Phalle

Chapter 1. A Reckless Shitamachi Native

(Translator’s note: Shitamachi “Lowtown” district means the lowlands in Tokyo such as Asakusa, Shitaya, Kanda and Nihonbashi where merchants and artisans live and work.)

A Girl on Ueno Hill

A girl, impressive for her jet-black bobbed hair and sharp, thick eyebrows, was walking tall on Ueno Hill like a boy in spite of her tiny stature. She was followed by her two younger sisters. These three girls were the daughters of the owner of Japanese-style restaurant Hanaya, just a stone’s throw from Ueno-Hirokoji; the big sister’s name was Shizue, the middle sister Chieko, and the little sister Miyoshi.

Approaching from the other side was a big boy who appeared to be a neighborhood bully with his minions in tow.

“Those boys bullied Ken across from our house,” whispered Miyoshi.

“Hey, look! Here come the stuck-up sisters sashaying!” The boys jeered at the girls. The three sisters wore matching light-blue middy one-piece dresses and ribboned straw hats, which were quite fashionable back then, a possible reason for the mocking by the boys. When they were about to pass each other, Shizue reprimanded the bully in a loud voice, “Stop talking nonsense!”

“What? Who do you think you are!” he reacted.

“So, what will you do? Huh?” Shizue shot back. His henchmen were ready to attack. The two kid sisters, now scared, pulled Shizue’s sleeve, “Let’s go home, Big Sis.”

“I dare you we settle this in a one-on-one fight! Come back here later,” she challenged the bully.

“Are you sure you can handle him, Big Sis?” the sisters asked Shizue anxiously, but she laughed it off, “No problem. No problem.”

Evening came. The little sisters had been lounging at home reading books, completely forgetting Shizue’s promise to fight. Shizue sneaked out of home and climbed Ueno Hill. The bronze statue of Takamori Saigo, famed samurai/politician [1828-77], was looking her way. With the figure in sight, Shizue summoned up her courage, “All ready!”

The bully was already there. Held in his right hand was a wooden stick, which made Shizue really angry. “Coward! You call yourself a man? If that’s the road you take …”

Shizue quickly picked up a small rock that was there, and threw it at the bully. The rock hit him just above the right eye. He was crying loudly, bleeding. She’s easily won, but also immediately realized the seriousness of situation.

“Shoot. I’ve done it again……”

Shizue was a bookworm and especially enjoyed the Tachikawa Bunko series that was typically popular among boys. The fantasy featured ninjas such as Sasuke Sarutobi and Saizo Kirigakure, as well as feudal warlords such as Miyoshi Seikai Nyudo. Those heroes were masters of cunning and outwitted their enemies. Shizue didn’t find that kind of wisdom evil. There were always good lessons in the stories. Precepts such as “To see what is right and not to do it is to lack courage” and “How can a small bird understand the aspirations of a large bird?” inspired her; in fact, they inspired her so much, while fighting an opponent, she sometimes muttered to herself, “You, little bird …” Thus, being a booklover helped Shizue nurture a fierce sense of heroism. However, she acted upon it too often.

“Are you okay?”

Shizue anxiously asked the bully boy, which made him cry louder. She heard some voice. Instinctively believing she’d be “scolded,” she fled into the bushes quickly.

A passerby found the crying, bloodied boy. Soon, a commotion ensued. However, the pride of the bully somewhat prevented him from revealing to anybody that he had attempted to fight a bare-handed girl with a wooden stick and ended up being injured by her. Shizue continued to hunker down in the bushes until quiet was restored.

When people were finally gone, she crawled out of them and walked down Ueno Hill under the moonshine. “Not very wise to hurt anybody, I should know,” she thought.

Shizue was ten years old.

The Japanese Restaurant Hanaya

Shizue Kuroiwa was born on March 21, 1931 in Kanda, Tokyo. She spent her childhood in prewar years at the Ueno Hanaya. In those days, the neighborhood was called Shitaya Sukiyacho lined with various stores, restaurants, soba noodle shops, geisha teahouses and geisha houses; along with Shimbashi and Yanagibashi, the area was a lively entertainment quarter continuing from the Edo period. Throughout the year one could hear the sound of shamisen. Geisha and men of the pen went by on rickshaw. The town was full of a sophisticated, fashionable atmosphere.

Walking immediately south from Shinobazu Pond to Ueno Hirokoji and turning west, the second building was the Ueno Hanaya, a three-storied wooden one. It faced Shinobazu Street and Ikenohata Nakamachi Street. Shizue’s father, Arae, was allowed to start his restaurant as a branch by the chef-owner of Hanaya in Ningyocho. The chef-owner of the main restaurant, Tohei Okawa married the daughter of the owner of the famous restaurant Hamadaya when he was young. Hanaya was named after his bride, Hana.

Arae’s father, Yoshitaro, a son of the owner of the restaurant Kaneda in Ueda City, Nagano, also became a cook. Since he had been a close friend of Okawa in the Navy, he decided to go up to Tokyo and then opened Hanaya in Shiba.

The Ueno Hanaya had a big eye-catching signboard to the side of the restaurant that read, “This is Hanaya, the Local Specialty Restaurant in Ueno.” Shiro Otsuji, a popular and accomplished comedian and friend of Shizue’s mother, Chiyoko, thought up the phrase; Chiyoko, with her kimono sleeves tucked up, had written it in bold, calligraphic brush strokes.

Inside the restaurant, there were Japanese-style paintings by Tsuguji Fujita, Yumeji Takehisa and others, on the left wall, and tables made from one piece of hinoki cypress were neatly lined up. On the right side was the counter on which, a large British-made cash register, too heavy even for three adults to lift, sat in a dignified manner. Upstairs, gleaming Nachi black pebbles were laid in the middle of the floor; there were another three or four hinoki tables in the room with an elevated zashiki on either side. The third floor was the craftsmen’s room. From the street outside, one could see the Japanese plum wood carving decorating the big window. It is said to be created by the younger brother of Okawa, owner of the head restaurant.

At Ueno Hanaya, the top selling line was double- or triple-stack bento box lunch. The ingredients consisted of crispy tempura, fresh sashimi, boiled vegetables, sweetened and soy-flavored omelet. It sold very well because of its delicious taste and reasonable price. Cooks at Hanaya lamented about busyness by chanting, “Man-yasu is a cook’s devil, Hanaya is a cook’s living hell, and Hakuun-kaku keeps cooks barely alive.”

Since the neighborhood was a lively entertainment quarter, some of Shizue’s schoolmates were adopted children to a geisha house or a geisha teahouse. Once, Arae found Shizue having gone to see a friend at a geisha teahouse and scolded her, “Don’t visit a bad place like a geisha teahouse!” However, Arae himself seemed to have been at such places at times.

Ueno Nikkatsu-kan, the cinema hall opposite to Hanaya, was situated at the corner on the east end of Shinobazu Pond. Shizue and her family lived next door. There also was the “Kurobei-san” restaurant/ryokan (Japanese-style inn). Customers from Yoshiwara took a bath, had a dinner and stayed overnight there. Every night, one could hear the ryokan staff holler, “Show another guest in here!” At night, a horse clopped on its way with the feed for animals in the near Ueno Zoo. This neighborhood was a full, peaceful and happy atmosphere.

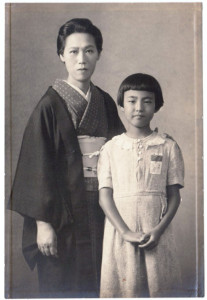

Seven-year-old Shizue (center) with her sisters.

Mother and Shizue

At age ten, Shizue was a vivacious and brave girl with a strong sense of justice. But she was different in her younger years.

“You must stay there until you apologize!”

One day in her preschool years, Shizue was scolded by her mother, Chiyoko and thrown into the dark and narrow storage space under the kitchen floor. Mother closed the floor board, laid out a zabuton (floor cushion) and sat on it. Shizue shut her eyes tightly and curled herself up.

“Let Big Sis out. Mom, please! Let her out!”

Shizue could slightly hear her younger sisters, tearfully pleading to Mother, but not Mother’s voice.

“I hate Mom! I’ll never apologize to her. It’s not just my fault.”

Mortified, tears began to well up in her eyes. Slowly and timidly, Shizue looked around. One by one, things around her such as pots, pans, kettles, and large jars started to take shape in the semi-darkness. She kept gazing at them. They, in turn, were smiling back at her. “I’m not afraid of you guys … at all,” she said, acting tough. But those images were unbearably frightening to the delicate heart of a young girl.

“Mom’s always nicer to my sisters! She never cares about me.”

Before long, she felt hot around the eyes. The pots and kettles began to bend like rubber.

Shizue must have fallen asleep while crying. All she knew was when she woke up, she was in futon bed. What happened was this: “Aunt” Okura, the hired helper for house chores, had rescued Shizue from under the floor while Chiyoko was away at a Japanese dance lesson.

Mother Chiyoko was born a daughter of the owner of Uoharu, a big Japanese-style restaurant in Jimbocho famous for having a big stage. Chiyoko was a beautiful woman with slanted eyes on a slender face. As the holder of a diploma in Japanese dance, she had the stage name of Mitsuharu Bando. She was versatile, excelling not only at playing the shamisen but also in calligraphy and drawing/painting.

Shizue often rebelled against Chiyoko’s way of discipline. She felt that Chiyoko cared for her sisters a lot more than for her. Occasionally, possibly because of Shizue’s stubborn nature, Mother slapped or beat her. She couldn’t open up to the ever-nagging mother. Eventually, she tended to hold her tongue, and even when she opened her mouth, she’d be contrary to her own mind, saying, “Nothing,” or “No, thanks. I’m good.” Mother, on the other hand, found such attitude “un-childlike” and irritating. She didn’t know how to unlock her daughter’s mind, and, as a result, was inclined to give her the cold shoulder.

When Shizue was very young, she was physically small and had a delicate constitution; she was a light eater. But Mother wouldn’t allow her to be a fussy eater; she was relentless. Perhaps this was because Mother wanted her to grow up in good health since Chiyoko was also physically delicate and weak when she was young. Typically, if Shizue left some food unfinished, Mother would present an extra-plateful of the same food. If Shizue did nothing, Mother would warn her, “You’re not allowed to leave the table until you’re finished with it!” and kept strict watch on her.

One day Shizue saw her opportunity and ran away to Aunt Kitagami in Oji.

“I really don’t know what to do with that girl.” Mother gave a sigh of resignation.

Aunt Kitagami was Arae’s cousin and very much doted on Shizue. Aunt Kitagami had two sons, Hiroshi and Keizo. Typical girl activities such as playing house were not Shizue’s cup of tea. Rather, she enjoyed playing bei-goma tops and chanbara sword fighting with the Kitagami boys. Thus, it’s almost understandable that when Shizue was yelled at by Mother, she often escaped to the Kitagamis.

The Kitagami family took great care of Shizue and never scolded her. She could stay genuinely relaxed. By contrast, the living with Mother at home grew increasingly painful.

Unhappy Early Childhood

If there was anything that could take her mind off this, it was books. Books healed her mind. She was absorbed in reading all day long. Small kana readings were printed along the Chinese kanji in those days, so she could read and understand even books for grown-ups. She read books while walking on the street or climbing Ueno Hill. Even after enrolling in elementary school, Shizue’s book obsession stayed unabated, neglecting her studies.

Only once, she was harshly scolded by her father, Arae. It’s one of her vivid memories.

He was a man of old-school artisan temperament and strict with his staff members. Yet, he was very sweet with his daughters. As the busy master of his restaurant, he left all child-rearing to his wife and “Aunt” Okura.

One day, Chiyoko confided to him, “Shizue does nothing but read books after school. She just reads in the dim room in the house. That may explain her weak constitution.” Mother sounded frustrated.

Father looked troubled while listening. Then, all of a sudden, he stood up, grabbed the book from Shizue’s hand, and threw it out the second-floor window. Moreover, one by one, he began throwing out other books around her. Arae was flushed red in the face with anger. Stunned, Shizue was speechless.

“Stop indulging in reading only! It’s not good for your health! I will discard other books, too, if you continue to read them!” he blasted. Shizue apologized, “I am sorry.” She was feeling so much regret not necessarily for the indulgence of reading, but more for making her father angry.

During those days, she couldn’t truly enjoy school, either.

In the first Drawing class in elementary school, the teacher said to the pupils, “Draw a picture freely. You can pick any subject you like.” Everybody reacted cheerfully, “Yeees!” Shizue was also excited about making her first drawing at school. The pupil next to her was drawing a picture of an electric train. The one in the back seat was drawing her mother.

“What shall I draw … Oh, I know!”

She began drawing a goldfish peddler carrying metal basins on a pole, whom she happened to witness the other day.

“He was funny and high-spirited.”

She kept drawing fast. She added a dialogue balloon over the peddler’s head and filled in his words, “Kingyo ehh Kingyo! (Goldfish … Yeah, Goldfish).”

“Wow, nicely done,” Shizue talked to herself, satisfied. At that instance, a fist hit her in the head.

“Ouch!”

She looked up placing her hand on the head. The teacher was making an angry face.

“Who told you to draw a manga? Stand in the corridor for your despicable actions!”

The teacher was furious; he violently dragged her out to the corridor. She couldn’t understand what was happening.

“He told us to draw anything we like…”

For the duration of the entire class, Shizue was forced to stand up in the corridor.

After this experience, she absolutely hated the Drawing class. Whenever the teacher came near, she slumped over the desk to hide what she was drawing. The teacher determined that she was acting in a suspicious manner and ordered her to stand up in the corridor.

Due to such lack of understanding from adults, Shizue was increasingly absent from school. At the same time she also felt she didn’t belong at home. Playing hooky, she began to frequent places such as Ikenohata, Ueno Hill, and Asakusa.

Shizue’s early childhood was an unhappy, gray world.

Father (extreme left) and Mother (third from left) in Numazu

Death of Her Mother

The only good memory of being with her mother was the time the two went to Shinobazu Pond to see lotus flowers. The pond was fully carpeted with lotus flowers, which were swaying softly in the breeze, on stalks taller than Shizue’s head. Her mother, clad in white summer kimono, was holding Shizue’s hand and explained to her.

“Lotus flowers bloom with a popping sound.”

“Really?”

Shizue’s eyes grew in amazement.

“It’s true. Look, there are so many flowers here. So, early in the morning, people around here can hear ‘pop, pop, pop’.”

Shizue wished she could catch the sound someday.

However, her mother’s health gradually deteriorated from those days. Naturally delicate, she often spent her time sick in bed. Fastidious and perfectionist by nature, Mother got irritated with her condition and became increasingly depressed.

Her family and friends thought Chiyoko should recuperate in a place with clean air. Mr. Okawa, the owner of the head Hanaya, was kind enough to build a house for her on the premises of his parents’ home in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture. Chiyoko moved there shortly afterward.

Shizue seldom visited her mother because she thought, “Mom won’t be happy to see me.” Even when she went to Numazu, she stayed with her mother only for a brief time.

“Why is Shizue like that? She came here after a long time and never stayed for long.”

Chiyoko would complain to Okura who took Shizue with her. Shizue’s sisters were playing quietly by their mother’s bedside.

“She never shows childlike qualities like being spoiled or throwing a tantrum.”

“Don’t worry. She will change as she grows up,” Okura answered.

Shizue may have been a difficult child to her mother. When they saw each other, they seemed to be offended by each other. It was not that Chiyoko lacked affection for her eldest daughter. Yet, Shizue always felt she was not loved by her mother.

In May of 1940, Chiyoko passed away. Her mother was thirty-three years old. Shizue was nine years old.

Shizue and her family went to a crematory near Numazu. A narrow wisp of smoke was rising for hours from the rustic crematory in the mountain. Under May skies, ripe golden raspberries displayed their bright colors. Shizue bade her mother an eternal farewell.

A Life with Her Father

After her mother’s death, the life with Father Arae and three daughters began.

Father was a well-built, stout man who wore black-rimmed spectacles. Though a man of few words, he said what needed to be said. He was very caring to his apprentices, and, in addition to cooks, he had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances.

Shizue and her father had a lot in common. Both loved animals and fishing. They had many animals and birds such as a spitz dog, a terrier, a Sakhalin dog, cats and Japanese white-eyes.

Shizue frequently went fishing to Shinobazu Pond with her sisters. When they fished near Benten Island, they could catch only little shrimp. The sisters grew bored, saying, “Big Sis, let’s go home now.” But Shizue usually answered, “Not yet. Not yet,” just the way Father said.

Father also liked baseball very much. He supported a youth baseball team, and belonged to a sandlot baseball team, which consisted of store and restaurant owners. Teammates included Bunbei Hara who was the chief of Personnel and Training Bureau, MPD, and later became the President of the House of Councilors. One day, Shizue and her sisters went to see their father’s baseball game on Ueno Hill. They saw a little overweight man chasing a ball desperately in the outfield. That man was their father. The girls cheered over the fence. “Let’s go, Dad! Let’s go!”

One autumn day, Father said, “Let’s go matsutake mushroom-gathering to Shinshu (Nagano Prefecture).”

“Yeah!” Shizue was very excited.

“You can bring your friends,” he said. As an only child, Arae felt lonely when he was very young. So he loved doing things together in company with many friends.

Father planned large group trips, consisting of his family, neighbors and friends, and paid all the costs himself. He was a man with a big heart. After the matsutake mushroom-gathering, they made a fire, grilled the freshly picked mushrooms and pork in the mountain. They tasted really good. At dusk, they walked down the mountain to see a field of susuki pampas grass swaying in the breeze.

Gradually Shizue grew cheerful and felt free under her father’s influence.

A Memory of Numazu

In the summer, Shizue and her sisters stayed at Mr. Okawa’s parents’ house in Numazu and played with Mr. Okawa’s children, Fusako, Motchan, Yuchan, and his granddaughter, Masako.

There was a pine grove in front of the Okawa residence. Past this, the Senbon Beach and the Suruga Bay spread out into view. Mt. Fuji could be viewed from there. Shizue and the others sat on the Senbon Beach, a gravel and shingle beach, put the feed between shingles and chanted a spell, “Jooni, konnya, niccha, kuchaka.” Then they fished little shrimps. In the morning, they picked cucumbers and tomatoes at Okawa’s farm, put them into a net and threw the net into the shallow water. By noon, the vegetables were nicely cooled and perfectly salted.

Mr. Okawa expanded Hanaya in his lifetime. A Meiji man with strict values, his motto was, “No work, no dinner.” He ordered Shizue and other children, who were there to play, to help the adults. He could be scary to the children, but whenever they visited him, he welcomed Shizue and her sisters by bringing out a ship with a dragnet. As Arae, Mr. Okawa’s brother-in-law, Motchan and Yuchan drew hard the dragnet, the net narrowed down. Inside the net, marine creatures including anglerfishes, sea brims, octopi were jerking and flipping.

The sea stretched as far as the eye could see and Mt. Fuji stood high. The Numazu landscape was Shizue’s second home. While admiring this marvelous view, she wondered how her mother used to feel when she was there.

The three sisters and their relatives

The Group Leader of the Three Sisters

“Hey Big Sis, tell me a story. I can’t sleep without one of your bedtime stories.”

Miyoshi begged Shizue. Shizue told a story to her two sisters almost every night. Sometimes, the story was staged inside the former exposition building with a ghost on Ueno Hill. Sometimes the story was adapted from Pinocchio. For Shizue, an avid reader, storytelling was her forte.

One night during a ghost story, they heard a strange bang from the street. The sound came repeatedly.

“A ghost is coming!”

The three sisters were shaking under the futon bedclothes. The sound gradually got louder and then died away.

“Let’s make sure if that was coming from a ghost,” Shizue said.

“No. I’m scared,” Chieko opposed.

“You will be eaten by the ghost,” Miyoshi said.

The three sisters looked timidly out of the upstairs window. A man who appeared to be a trainee Buddhist monk with a ringed staff was disappearing into the darkness.

“Aaaah!”

That was an extremely scary scene for the kids. Was the trainee monk visiting Kan-eiji Temple? Even in those days, trainee monks were rarely seen in Shitamachi.

Perhaps the girls were too used to believing imaginary stories to distinguish reality from fantasy. Before long, Shizue stopped telling ghost stories.

Shizue was the group leader for her two kid sisters. The three played explorers: they built a secret base on Benten Island in Shinobazu Pond and hid their favorite things or went in and out students’ laboratory in the basement of the National Museum of Nature and Science.

One day, they were playing in the playground on the roof of Matsuzakaya Ueno department store.

“Whoa! I can see Granpa’s restaurant!” Shizue shouted.

“Yeah! I can see Grandma having lunch!” Chieko said.

At that time, Yoshitaro and Chiyo, their grandparents, were managing Hanaya in Shiba. However, though the two locations were connected by one straight road, there was no way they could see the restaurant from the department store, which was nearly ten kilometers away.

“Let’s go to see Grandpa and Grandma!” Shizue suggested, and the sisters agreed. “That’s a good idea. Let’s go!” The sun just passed over their heads. The three girls set out in high spirit.

Despite their auspicious beginning, they soon realized that they were only young children. They kept on walking, but they couldn’t make it to the destination. Finally, the sun began to set. The younger ones became exhausted; they announced tearfully, “I can’t walk any more.” There was a police box in front of them. Shizue said to Miyoshi, “Maybe we’re lost. Ask that policeman about how to get to Shiba.”

The policeman told the three to stay and wait. Soon, an employee from the Ueno Hanaya came to pick them up. Meanwhile, at home, the Hanaya staff began to worry about the missing three sisters. It caused a major commotion. Before going home, the employee decided to drop in on the Shiba Hanaya and let them see their grandparents, who were ecstatic, “So glad you came! Happy to see you!” Finally home, the sisters were afraid Father would scold them. But, he didn’t.

After this incident, Shizue felt that she could do anything she wished to do. Many called her “a reckless Shitamachi native.” This was about the time Shizue demonstrated her tomboy qualities against the neighborhood bully on Ueno Hill.

Shizue and Grandmother Chiyo

Shizue and Rakugo

(Translator’s note: rakugo is the traditional Japanese comic storytelling by a single entertainer)

There was a rakugo hall, “Suzumototei” near Ueno Hanaya. Now in elementary school, Shizue went to the hall almost every night. Every time she said, “I’m from Hanaya,” the hall staff would let in the little neighbor free of charge. Entering through the back door, she sat in the front row while holding her geta clogs. She eagerly listened to rakugo told by Bunraku Katsura, Shinsho Kokontei, Kimba San-yotei, and many others. She always doubled over with laughter.

One day, “Aunt” Okura asked Shizue, “Could you go to the thread and yarn shop to buy red and white thread?” After shopping, Shizue said to the shopkeeper, “Keep the three yen change, mister.” “Thank you!” he said. She felt great, as if she was an adult by tipping a storeowner.

However, once at home, Okura severely disapproved of her behavior. “Don’t be so sassy, kiddo! Someday you’ll pay for it even if the amount was three yen. No meal tonight until you get back the change.”

“What shall I do?” Shizue was pacing back and forth in front of the thread and yarn shop. She can’t take back what she already told him. She thought hard and hit upon a good idea, “Eureka!”

She hurried home and performed rakugo in front of her sisters. “Well, I’m going to tell you a funny story.” She could do this because she had learned the story by heart. Her impassioned performance kept her sisters laughing.

“Now, will you two pay me the three yen admission fee?” she said.

“What? We didn’t expect a fee … No way,” the sisters protested.

“Pay it to this poor entertainer, please.”

Needless to say, Shizue gave the three yen to Okura as the change from the thread shop.

The Shadow of War

In 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and plunged into the Pacific War of World War II. Although the shadow of war was creeping up on Tokyo, children in Shitamachi felt that war was being fought in somewhat remote regions. They were too absorbed everyday in playing and getting muddy. As Japan began to invade Pacific islands, rubber balls were delivered to pupils at elementary school. Children thought simplistically, “Nice things can happen to us if we win the war.” They had very little doubt that Japan would go on to win the war.

Next year, however, U.S. bombers started raiding the mainland of Japan. Increasingly, the war was threatening their daily lives.

In 1943, Shizue enrolled at municipal Shinobugaoka Girls’ High School, located on the former site of daimyo’s garden Horaien in Asakusabashi. She met new friends and new teachers. At once, she loved the school and the new subjects, English in particular. English classes were continued at girls’ schools because they “need to know the enemy if we want to win the war against it.” To Shizue, English was more the entrance to the unknown world than the enemy nation’s language, and she studied it very hard.

In 1944, the evacuation of schoolchildren started. Shizue’s two sisters were elementary school pupils and evacuated to Aunt Kitagami’s parents’ house in Ueda City, Nagano Prefecture. The U.S. B-29 bombing of Japanese cities grew continuous and intense. In Shitamachi, adults removed the roofing tiles and shingles so that the flames caused by a bomb explosion would not spread. Only skeletons of school buildings were left. They removed roofing tiles of Kuromon Elementary School where the Kuroiwa sisters went. Houses neighboring the elementary school were torn down. The residents were forced to evacuate.

Hanaya became the emergency kitchen. Arae and the staff were always busy preparing meals such as onigiri rice balls and hardly had time to sleep. Every night, people including the Chief of Shitaya Ward, the stationmaster of Ueno, and Bunbei Hara as the chief of Personnel and Training Bureau, MPD, gathered at Hanaya. They huddled closer and discussed in whispers.

With her sisters gone, Shizue was lonely at home. Girls’ high school was her only pleasure. The students attended classes on weekdays and wrapped balls of cod-liver oil separately on Saturday as their role at a so-called School Factory.

Often when she was in bed at night, the air-raid siren sounded. Her father was at Hanaya. She sprang to her feet, covered the head with a metal washbasin, pick up her dog and dashed into an air-raid shelter under Ueno Park. Shizue was terrified. This had become the daily reality for the area; nobody had any idea what tomorrow would bring.

The Great Tokyo Air Raid

Shortly after 0:00 a.m. on March 10, 1945 — the time and date Shizue would never forget. The ear-piercing sirens wailed intermittently.

“Air-raid sirens!”

Shizue jumped out of the futon bed. Her sisters were at home; they had returned from Ueda temporarily for the school registration in Ueno.

“Chiyoko, Miyoshi, get up! We’ll hide in the air-raid shelter under the restaurant,” she cried while putting on her air-raid hood. Outside, the air felt eerie and the north wind was blowing hard. She looked up at the sky intently.

“I’m going to see what is happening from the roof of Nikkatsu-kan cinema hall.”

She started running up the stairs of the cinema hall right next to her home. Her sisters followed her. From the roof, they could see the sea of flames in the Fukagawa area. Firebombs exploded violently one after another like fireworks deviating from the orbit and attacked their town with a piercing sound. A group of B-29 bombers, normally flying high, flew low this time, showing their dark-red bellies. Without a word, the three sisters continued to stare at the sight, terrified.

“The flame is coming. It’s too dangerous. Let’s go to the restaurant,” Shizue suggested. The three entered the restaurant. Inside, accompanied by their father and the restaurant staff, they rushed into the underground air-raid shelter, which had been dug out inside the restaurant. The shelter was built with concrete and had a large iron door on it. Originally it was a storage space to keep rice and other foodstuffs for the restaurant menu. Everybody drew closer and huddled against each other.

On that day, approximately three hundred B-29 bombers dropped as much as 1,700 tons of incendiaries over Tokyo, centering around the Shitamachi area. A strong northwesterly wind blew with vicious intensity. Everywhere, the wind whipped up tornado-like flames called “fire whirlwinds,” trapping thousands of people and burning them to death. Some tried to escape to Sumida River and Ueno Hill; those who jumped into Sumida River died of hypothermia or drowned. The river was filled with corpses. The air raid claimed 100,000 lives in a span of just two hours.

Inside the shelter, Shizue kept shivering, terrified. She could do nothing but pray, “Please make them go away fast. Please. Save every one of us.” It was sheer hell.

This was the Great Tokyo Air Raid, a tragedy to be discussed and passed down for generations.

Next day, Shizue, with a sooty face and in a black coat, was at the empty Girls’ High School, staring at the school building for a long time. Miraculously, the building had escaped the fire. But the school was shut down that day.

The Evacuation

Town had been reduced to burn-out ruins as far as the eye could see. There was no longer any shape to the town. A number of trucks were going to and from Ueno Hill. Wondering why so many trucks were running, Shizue started toward them by walking through still smoldering building debris.

Piled high on the beds of those trucks were what appeared to be black logs. Shizue came to a halt. They were not black logs. They were charred human bodies. At the site, holes were dug up and the bodies were buried temporarily.

That scene haunted her for the rest of her life. Shizue could not comprehend why those innocent people had to be killed.

Hanaya escaped the fires. Her sisters returned to Ueno a little ahead of her. Her father and the cooking staff were busy providing meals to the local residents.

“You’d be in danger here. You, too, should go to Ueda,” her father said.

“No. I don’t want to go to the countryside. I’d rather help you cook.”

Shizue wanted to give assistance to Father in any way she could.

“Actually, you’ll be more of a burden to us. You’ve never made onigiri, right?”

Her father was right. There was nothing she could do there. She was angry at herself.

“My school has been closed down. I can’t study here …”

In the end, she decided to join her sisters in Ueda. Her father packed foodstuffs into her suitcase.

“Take good care of yourself, Dad. Promise me!”

“You, too. Look after Chieko and Miyoshi.”

Seen off by her father and the stationmaster of Ueno Station, a family acquaintance, she headed off to Ueda. Although the steam train was overcrowded, she could take a seat thanks to the good offices of the stationmaster.

Her father had rented a former tansu chest-cabinet shop for her in Un-no-machi, Ueda City. Shizue joined her sisters, and began to live not only with them, but also with Aunt Kitagami and her son, Hiroshi. Her another son, Keizo, had moved to Gunma Prefecture with his schoolmates as part of the government policy of collective evacuation of school-age children in preparation for the imminent air raids.

Shizue started working at a munitions factory under the policy of student mobilization. She and other girls sewed parachutes at the factory of Kanegafuchi Spinning Company (now Kanebo). Such an unfamiliar task was hard for them, but no one complained. Everyone endured the hardship collectively.

As the war progressed, the food became scarcer. One day, sugar surrogate was given to students at the factory. At home, combining the surrogate that Shizue brought home and the still remaining small amount of azuki red beans, Aunt Kitagami made sweet porridge (oshiruko). All the family shared a small portion of it.

“Good, isn’t it?”

They hadn’t smiled in a long time at this place of refuge.

One day, a lot of foodstuffs arrived from her father. Shizue crammed snacks and vegetables into her backpack and set out on foot for Maruko-machi, the neighboring town of Ueda City. At Maruko-machi, Michiko Saito, her senior by one year and nicknamed “Bear-san,” was working at a parachute factory also under student mobilization. Unlike Shizue, Bear-san lived in the dormitory, and had written her about their harsh condition of food scarcity. Painfully aware of it, Shizue felt that she must deliver some food to Bear-san as soon as possible. Thus, taking a long, sweaty walk was no trouble to Shizue. It was a brief, yet rewarding reunion with a friend.

After witnessing the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10th, Shizue never believed that Japan would win the war.

Air raids over Tokyo continued. In particular, the bombing on May 24th and 25th was carried out on a large scale.

“Wonder if Dad is all right and the restaurant, too. Hope my High School hasn’t been burnt down,” Shizue grew worried more and more.

“I saw many human beings burnt to death like black logs. How long can such a war continue?”

She felt a black lump of anxiety was growing and swallowing her.

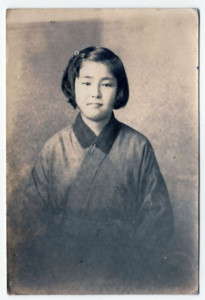

Fourteen years old Shizue in Ueda, a site of evacuation.

The Day the War Ended

On August 14th, Arae made a surprise visit to Ueda and said, “Tomorrow there will be an important broadcast.” Although he had a haggard face, he tried to act cheerfully. By that time, Shizue and her relatives had moved to a traditional Japanese-style house in Renga-cho in Ueda City. Grandma Chiyo had also moved there from Tokyo. Grandpa Yoshitaro died from gastric cancer in 1942 when the war was not as severe; after that, the Shiba Hanaya was closed down.

On August 15th, the family got together around the radio with Arae in the middle. They listened to the broadcast of the Emperor’s announcement of Japan’s unconditional surrender. All kept silent. Japan lost the war. There was so much static on the radio, but somehow, Shizue understood the gist of it.

She felt relieved. From now on nobody will have to die in war.

“War is over. At last. It’s over.”

Shizue and her sisters held each other in a tight embrace.

After several days, she saw a B-29 flying low when she was hanging laundry on the clothesline balcony. She grabbed a white shirt and started waving it frantically.

“It’ll finally be gone.”

She was overcome by deep emotion.

“Don’t come back. Never!”

Tears ran down her cheeks. Even after the bomber grew smaller and then disappeared into the blue sky, she kept waving the shirt.

“I have no time to lose. War is over. I’ll go back to Ueno,” Shizue thought.

In the early morning several days later, Shizue woke up her middle sister. “Time to be up, Chieko.”

“What’s the matter, Sis? It’s before five,” Chieko said sleepily.

“Listen, I’m going back to Tokyo. Take me to the station by bike.”

“Really? Going home? Alone?”

“Yes. I wanna see what has become of Ueno myself.”

Chieko pumped the pedals and Shizue got on the back seat. At the station, Shizue jumped onto the first train of the day.

Shizue was fourteen years old.

About the same time, one young man leaped aboard a train for Shinjuku at Matsumoto Station. His place of refuge also in Nagano Prefecture. Upon learning of Japan’s defeat, he couldn’t contain himself from the feeling of liberation and exaltation and jumped in a car without a ticket. His name was Tsuji Masuda, a metropolitan high school student.

→ Chapter 2. A Youth in the Postwar Ruins