*

Niki and Yoko

From a Shitamachi Okami to a Niki de Saint Phalle Collector

*

*

Written by Yuki Kuroiwa

Translated by Nasuka Nakajima

*

Chapter 8. Road to Founding the Niki Museum

Yoko’s Adoration Makes Niki Nervous

An airmail arrived at Niki’s studio in Soisy, France. One look at the handwriting of “Dear Niki de Saint Phalle” was enough to see that it was from Yoko. She had been writing to Niki several times a month.

After meeting Yoko in Italy, Niki had returned to Paris to concentrate on the treatment of her rheumatism. Meanwhile, Yoko was increasingly driven by the dream of starting a museum even more than before. In her letter, in addition to writing how anxious she was feeling about Niki’s condition, she expressed her plans passionately: “I want to introduce you to Japan by translating catalogues and delivering them to art museums and critics,” and “Not only in Tokyo but also in other cities, I’d like to host exhibitions.” The contents were basically the same.

Yoko had talked about her dream like a maiden, “I’ve been thinking about… founding an art museum for you in Japan.” When Niki heard that, she was happy indeed. Still, she had met Yoko only twice. Even though they had had a nice heart-to-heart talk, Niki was overwhelmed by Yoko’s fanatic adoration. Niki wasn’t sure how to judge Yoko as a person.

In those days, Niki was jetting around the globe on various projects. In 1983, she and Tinguely collaborated on a fountain on the Stravinsky Square, next to the Pompidou Center, and installed a large sculpture on the University of California, San Diego campus. Prior to them, she had painted the exterior of a new airplane in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

A lot of people wanted to meet and work with Niki. If she tried to hear all of them, her health would not hold out. On top of that, there had been more than a few sweet-talking, unscrupulous individuals who tried to take advantage of her.

Yoko’s admiration for Niki was out of the ordinary. Their first conversations were mainly conducted with an interpreter; Yoko had trouble making herself understood completely. But in her letters, she was able to express herself in a straightforward manner.

“Your art is as noble and beautiful as Mt. Fuji,” “I was destined to meet you and your works. You changed my fate,” and “I extremely fear that I might be disturbing you, who are engaged in sacred creative activities under God’s will.” Yoko could not stop praising Niki.

Niki found it difficult to completely relate to Yoko’s incessant adorations. Niki felt embarrassed and isolated, as if she was put up on a pedestal. Yoko’s overenthusiasm even frightened Niki.

Yoko’s Illness

Yoko sometimes drew pictures with Niki’s work in mind.

One day, Yoko felt a clenching pain in her chest and had difficulty breathing. She lay down on a sofa in the office. She broke out in a cold sweat and felt nauseous. Oyamada saw it and immediately called an ambulance.

It was a minor myocardial infarction. The doctor advised, “You have to have adequate rest and sleep. You’re not young any more. Reconsider the way you work. What you need is one month off from work, at least.” It was true that she had overworked. As a representative of Space Niki, Yoko had hosted domestic artists’ exhibitions one after another. Almost every day, she went on a bar-hopping spree with artists and visitors. In addition to that, she handled the management of her building, coffee shop and picture-book store, not to mention she was in the middle of a trial involving her late father being a joint guarantor. She went home late every day.

There was little progress in the relationship with Niki. There seemed no sign that Niki would respond to Yoko’s feelings. She continued letter writing, not aware that Niki had been frightened by Yoko’s overwhelming approach. Under such circumstances, fatigue and stress had built up in her body.

“I might as well take a long rest. Why not spend time in Hakone where I can see Mt. Fuji? I’ll forget about my work for a while and do painting. I always wanted to paint large pictures.”

Yoko used to spend summers in Numazu in her childhood. She felt very nostalgic about the sight of Mt. Fuji. On the doctor’s order to take a month-long rest, she bought oil paints, an easel and canvas at an art supply shop and left for Hakone.

Yoko stayed in a hotel room with a commanding view of Mt. Fuji. The room faced Mt. Fuji straight on. Gazing at its majestic shape, she started to feel foolish about fretting over the small matters. She indulged herself in painting. She drew lines on a canvas in silence. It was nothing but fun. She finished several pictures of Mt. Fuji. She also tried her own versions of Niki’s works as an homage to her.

One month into her recuperation, near its end, Tsuji came to Hakone to visit her. He had been promoted from the managing director to the president of PARCO in 1984. Seeing Yoko’s pictures, he commented, “They are pretty good.”

“I tell you what. I’m going to hold a two-man show with Ban-no (Tsuji’s old friend). Why don’t you join us?”

Thus, the Space Niki gallery opened a three-person show called “Saint Trois.” Yoko’s pictures created a sensation for her unique use of colors and bold compositions; one of them was featured as “The Painting of the Week” in a weekly magazine. Tsuji grew very jealous and banned her from going to the PARCO drawing workshop.

Nonetheless, Yoko was regaining health both physically and mentally.

Que Sera, Sera

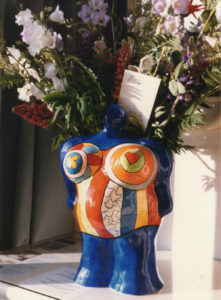

Niki’s surprise gift was delivered to Yoko’s hotel room during her trip in 1985. A message was attached to the vase created by Niki. (photo by Yoko)

Niki had two children. She gave birth to Laura at age 20 and to Philip at 24. Deciding to live as an artist, Niki divorced her husband and American writer, Harry Mathews [1930 – 2017], when she was 30; Mathews took the custody of their children. Although the mother and children were separated from each other at this point, when they grew up, they often visited Niki, and appeared in Niki’s films and helped her publish books.

When Yoko visited Paris for the first time in 1981, Niki introduced Laura to Yoko. Laura looked to be only 17 or 18 to Yoko; she was 30, beautiful, gentle and sensitive. Before Niki, Yoko could not help being excited, often too excited to communicate. In contrast, Laura got to know Yoko’s true self from the beginning. Laura perceived Yoko’s unique sense of humor as well as her sincere and passionate personality early on.

On one occasion, Niki spoke to Laura.

“I’m frightened by Yoko. She said my works changed her life. Do you believe that’s possible?”

Laughing, Laura said, “Are you really frightened by that Yoko? Let’s see … Why don’t you ask her to sing a Peggy Lee tune when you meet her the next time?” She had heard Yoko humming her song.

In 1985, Yoko traveled to France and other countries, including Switzerland, Belgium and Italy, to visit Niki exhibitions. Niki and Yoko were reunited.

Yoko had been singing in the car. Niki was captivated by Yoko who did a brilliant impersonation of Peggy Lee. Niki was surprised, asking Yoko, “Are you using magic, Yoko?” Yoko continued to sing Doris Day’s Que Sera, Sera. The future’s not ours to see, Que sera, sera, What will be, will be. The car was filled with women laughing.

Niki cried in excitement, “You are a great performer, Yoko. You remind me of Giulietta Masina.”

“When I met you for the first time, I felt it was not our first meet. I’m wondering if we were sisters in our previous lives,” Niki said.

“If so, I wouldn’t collect your works. I don’t think we were a parent and a child, either. You once said that perhaps you were burnt to death for being a witch in your former life, Niki. My theory is that I was the judge who sent you to the stake, which is making me atone my sins in this life,” Yoko replied.

“Really? That explains why I felt for a long time that I had been crucified. Now, I understand.”

“It’s scary, isn’t it?” Yoko looked into Niki’s face.

“I love scary stories!” Niki answered.

The two kept laughing in the car. The ambivalent feeling between them dissipated.

Big Head

Big Head displayed on the first floor of Central Building 21 which housed Space Niki (photo by Masashi Kuroiwa)

One of Yoko’s destinations was a Niki de Saint Phalle exhibition in May at the Klaus Littmann Gallery in Basel, Switzerland. Yoko attended the opening ceremony, holding a big lily bouquet. Yoko’s long black scarf was embroidered with big lilies as well. “What a lovely scarf, Yoko!” Niki said. They could exchange only a few words before the visitors flooded into the gallery. Yoko wished she could talk more with Niki, but she knew she couldn’t monopolize her. Yoko collected herself and went around to see the exhibited works.

During this trip, Yoko wanted to buy Niki’s larger works. The gallery showed many fascinating works including TV on the Brain.

While Yoko was enjoying them, the gallery owner approached her.

“Each and every piece is precious, Madam Masuda. All were made in the 1970s,” he said. The name, Yoko Shizue Masuda, who was said to manage a gallery named after Niki, had gradually reached the ears of Niki de Saint Phalle dealers in Europe.

He added, “There are more works in the neighborhood park. If you’re interested, I’ll be glad to show you round.” Yoko said, “Yes, please. I’d definitely like to see it.”

A work shaped like a female head was placed in the spacious park. Even among Niki’s large sculptures, the head was particularly large. Children were playing around it. With red hair, goggling eyes, a big nose and green lips, it was a high-impact work of art; one could call it even bizarre. Yoko fell in love with it at first glance. A head without body, that’s hell. Don’t just think with the head. Take action. Yoko felt as if she had heard such intense messages.

Thus, Big Head, an approximately 8 feet long sculpture, joined the Yoko Shizue Masuda collection. Yoko purchased four works at this exhibition.

Dragon in the Garden of Nellens’ House

Next, Yoko visited Knokke-le-Zoote, a beautiful town by the sea in Belgium. In June, a Niki exhibition was held at the casino hall managed by Niki and Tinguely’s longtime friend and Belgian artist Roger Nellens [1937 – ]. The Nellens family is an ardent admirer of Niki and collected her works for two generations.

The opening ceremony was followed by the celebration party at the Nellens house. Thick woods occupied a part of the residential area: the estate belonged to the Nellens. There were orchards and stock farms on the premises. The children’s play house, Dragon, that the Nellens had commissioned Niki to create for their son, stood in a dignified manner adjacent to their home. It housed a ping-pong table among other things, and stuck out its “sliding” tongue. The guests with glasses of wine in their hands were roaming the garden or going in and out of Dragon.

Inside Dragon, Yoko found Niki in formal dress. Above her head, was a Tinguely’s Lamp constructed with skulls of sheep and cows offered by Roger and junk from iron farm implements. Multicolored illuminations were decorated on the ropes. To Yoko’s surprise, attached to one of the ropes were half-dried laundry items such as purple panties, a white brassier, black socks and a sleeveless undershirt.

“What are these?” she asked Niki teasingly. Niki did her best to keep a straight face, trying to hide a wry smile. According to Roger, it took Tinguely two whole days without sleep to complete this work. He finished it just in time on the morning of the party. Tinguely called Niki in high and proud spirits. Niki’s cool reaction was, “They are way more boring than a washing line.” Tinguely became furious and ran out of the room. When he came back, he had a handful of underwear, which he had snatched randomly from the Nellens family’s clothesline. Then, he hung the underwear piece by piece, and said, “So, are you satisfied?”

Hearing this, Yoko understood that Niki and Tinguely enjoyed each other and their ideas; they even turned their arguments and trifle squabbles into an incentive to create works.

Yoko stepped out of Dragon into the glaring summer light and found herself surrounded with beautiful lush greenery. Yoko could see Niki’s work everywhere, in the garden, the sunroom and the main house.

Yoko squinted at the Nellens’ house once again. They commissioned an individual artist to build an entire house. True, they have the wherewithal for this. Still, how big-hearted and trusting they are! Perhaps, this kind of generosity stimulated Niki and has been a steady, encouraging force for her. Yoko had to ask herself once again, “What can I do for her?”

“Reserve” is “Cowardice”

Yoko had been chasing Niki in France, Switzerland, and Belgium. The last destination was the Tarot Garden. The construction had progressed much further than when Yoko visited it the first time. In 1983, the iron framework of the Emperor Tarot Card, No. 4 remained exposed. Now, its foundation was completely cemented.

The interior of the Empress Tarot Card, No. 3, was also finished. The art studio was completed on the first floor and the bedroom was inside one of the sphinx’s breasts on the second floor, as Niki had announced. The curved interior was all lined with mosaic mirrors. The sunlight was coming through several windows, shrouding the whole room. Yoko felt as if she were in the womb of her mother, giving her a mysterious sense of peace. Mirrors were also put in the kitchen. A Tinguely lamp was hung over the table made by Niki. Snake chairs circled round the table. The red-colored bathroom was equipped with a showerhead in shape of a blue snake’s mouth. Everywhere, Yoko could feel Niki’s sense of playfulness.

After lunching outdoors, Niki and Yoko had tea inside that Empress. Yoko blurted out her anxiety. It had been hanging over her head for a long while.

“I said I’d found a museum for you. It may not happen. My ability is so limited …”

At the Nellens’ residence, Yoko saw the luxurious houses and garden, and each of Niki’s magnificent works stood out against that background. She envied the Nellens. By stark contrast, Yoko had just began collecting Niki’s works with limited financial resources. She was beginning to feel that starting an art museum was just a wild, far-fetched dream.

Yoko was looking downward, feeling small. Then, Niki held Yoko’s hand and spoke softly and calmly.

“I don’t think so. You have the ability.”

Niki was looking at Yoko with affectionate eyes. Recalling this conversation, Yoko would write to Niki later:

At that moment, I was quite moved by your quiet manner. Your manner as such made me think over and over. I was really ashamed of my smallness… I mean the smallness which made me tell you words of excuse on the lack of strength.

I realized that the Japanese sense of “reserve” probably did not mean anything beyond “cowardice” or “excuse” to you. Since then, my memory of your calmness and serenity of mind, which I believe come from your real strength deep-rooted in my bosom and has always been encouraging me.

Once Yoko felt Niki’s affection and strength, she truly wanted to be like Niki.

“I’ve just stepped onto the road to founding the Niki Museum. I’ll take one step at a time. Even with limited capital, I have a big passion and a big dream.”

Advice from Two Friends

In the fall of 1985, three women were chatting and eating sukiyaki in Asakusa, Tokyo. Yasu Ohashi, a stage director and Yoko’s interpreter in Paris, Kazuko Koike, a creative director, who introduced Ohashi to Yoko in the first place, and Yoko. This day, they attended an Anton Chekov play directed by Ohashi.

“You must have collected a lot of Niki’s works by now,” Koike said.

“No, far from it,” Yoko replied. She had not been able to collect them as many as she wanted. Galleries had limited numbers of Niki’s works. And just because Yoko wanted one of them, she couldn’t easily buy it. Niki being a highly sought-after artist made it difficult to purchase any piece directly from her. Also, Niki’s assistant at that time was not very accessible to Yoko. For this reason, she reluctantly gave up buying rare ones from Niki’s early days that she had found at Niki’s studio. Collecting Niki’s work in itself was a long and hard road.

In order to launch a museum, Yoko’s collection was simply too small. Although encouraged by Niki’s words at the Tarot Garden, she was always frustrated and mortified by hampered museum projects.

“Why don’t you hold a show with what you’ve collected?” said Ohashi.

“No, no. My collection is still small and limited,” Yoko disagreed.

“Then, why not do it at my space?” Koike suggested. She was managing Sagacho Exhibit Space (now Sagacho Archive) on the east riverside of Eitaibashi, Koto Ward. It was an alternative space (non-profit exhibition place) for contemporary art.

“I saw Pierre Restany [1930 – 2003] the other day. We talked about my Space being diverse and good for Niki’s works,” Koike added. Pierre Restany was a renowned art critic whom Niki had trusted most, and Yoko had met at a Niki exhibition abroad.

Four years had passed since Yoko held a Niki exhibition at Space Niki. Koike’s words opened her eyes. I’ve been thinking only about protecting my treasure, Niki. That made me a blind snake. The advice of her friends considerably broadened her perspective. Yoko decided, “Even with my poor collection, I’m going to introduce the Japanese to as much of Niki’s world as possible.”

“Would you let me use your place?” Yoko jumped at Koike’s proposal.

Right after that, Yoko started preparing for the opening of Niki exhibition. She decided the suitable opening date to be April 1st, April Fool’s Day; Niki always said, “I see myself as ‘the Fool’ Tarot Card, No. 0.”

In this manner, two Niki de Saint Phalle exhibitions were simultaneously scheduled at Sagacho Exhibit Space and Space Niki for the duration of approximately three weeks and three months, respectively.

Two Simultaneous Niki Exhibitions

Nana-shaped bread served to visitors at the opening ceremony.

Niki’s works displayed at Space Niki.

The closing party of the successful simultaneous Niki exhibitions.

On April 1, 1986, the opening ceremony for two simultaneous Niki exhibitions was held with much fanfare at Sagacho Exhibit Space. In place of Niki, who was under the weather, her daughter Laura and her husband Laurent attended the party. The media focused on the beautiful Laura. The attendees included Taro Okamoto and photographer Nobuyoshi Araki [1940 – ] and his wife. Many pieces of Nana-shaped bread were spread over a large table; Niki’s symbolic figures in golden brown were placed as if they were dancing.

Sagacho Exhibit Space was located in the Shokuryo Building (former rice market facility), constructed in the early Showa period [1925 – 1989]. The exterior walls were covered with brick tiles. The floor was of bare concrete. Large arched windows created a retrospective atmosphere. The ceiling was16 feet high, which made the venue look very spacious.

Niki’s five large works including Big Head and TV on the Brain were installed there. There were various performances and the screening of Niki’s biographical film Daddy.

Many visitors were chatting in front of The Line of Conversation (1980). Yoko explained the work to them:

“With this work, Niki is stating, ‘Heaven is empty. Emptiness is me.’ Because she inhaled vapor and dust while working with polyester, she has been suffering from lung trouble and gone into respiratory distress. Since she wanted her works to breathe easily, she created a lyrical linear sculpture; she made it as if she drew a line in a unicursal manner. She wanted the air to flow freely around it. After completing this sculpture, she said, ‘Now, I’m feeling mystically united with myself, the air and the light.’”

Her collection used to be sitting in the warehouse. But now they’re appreciated by many visitors in such a spacious venue. Yoko basked in indescribable happiness. And she looked around those who were enthralled by Niki’s art.

“I recognized once again that the exhibition venue should be spacious. That high ceiling is very good. Usually exhibition halls in a museum have no windows, but I’d definitely like mine to be equipped with windows. Mirrors are used in many of Niki’s works. If the natural environment is reflected on mirrors on her work, that would be great.”

The image of her museum began to balloon in her mind.

Space Niki, the other exhibition venue, displayed relatively smaller pieces including prints. A Dream Longer than the Night, produced by Niki, was screened there. Daddy was also viewed and it was followed by a panel discussion.

Men and women of the hour participated the panel discussion: Kazuko Koike, Koichi Makigami (musician), Kazuko Shiraishi (poet), Chizuko Ueno (sociologist), Kazuko Matsuoka (translator), Suehiro Tanemura (critic), Hana Kino (actress), Saburo Kawamoto (film critic), Emi Wada (costume designer), Sachiko Yoshihara (poet), Eriko Zanma (media producer) and Midori Kiuchi (actress) and others. They discussed Daddy in pairs or in trios. Some appreciated it, some felt a rejection of its expression and others found contradictions in it. The discussion grew heated. Sometimes, panelists became sidetracked from the theme of Daddy. It offered the audience a good opportunity to think about Niki and her work. Later Yoko published a collection of the discussions.

It is true that many of the visitors to the simultaneous exhibitions were Japan’s art-circle personnel and critics. But the project was a big success with a large number of visitors. It served as a trigger for Yoko to hold “Cheerful Gifts from the Goddess of Eros: the Niki de Saint Phalle Exhibition” with her collection at Seibu Otsu in October, the same year. I’m glad I moved forward without hesitation. These exhibitions gave me some clue as to how to start a museum. Yoko was enjoying a sense of fulfillment.

By this time, Yoko had closed her coffee shop and picture book store. Now was the time to concentrate on preparing for the museum.

Increasing Approaches to Niki’s Works

In the spring of 1987, a man visited Yoko. He led the preparatory committee of a museum, aiming for a 1989 opening.

“We’d like to commission Niki de Saint Phalle a work and display it on the premises of our museum. Would you please contact Niki for us, Mrs. Masuda?”

At that time, Yoko had already been asked to act as an intermediary between Niki and another party. They wanted to commission Niki to create a work for the Design Expo ’89.

Yoko grew excited. If their wish came true, Niki would be known to people not only in Japan but also all around Asia. At the same time, though, Yoko worried that such offers would force Niki to overwork.

In May, Yoko visited a large scale Niki exhibition in Munich, Germany and then, went on to the Tarot Garden in Italy. Niki was intensely engaged in the creative activity there. She said that her first US major retrospective would be held in September at the Nassau County Museum of Fine Arts in the suburb of New York City. Niki was stoically devoting herself to production like a priest. Yoko hesitated to discuss the offers from Japan.

After taking a breath, Yoko began by spreading the papers. “These are detailed floor plans.” Niki looked at it and said, “These are not enough. When I display my work, I want to complete the work in France under my personal supervision, and place it in a beautiful natural environment in Japan. I want to see layouts and photos of the environments of the Expo and the museum.” Niki attached importance to the harmony between her works and the surroundings.

Unfortunately, after many twists and turns, these two Japanese projects did not materialize. What Yoko learned from this experience was one simple lesson: What matters most is Niki’s sensibility and health. Because of this, however, Yoko would continue to agonize over what to do, whether it came to the Niki Museum project or offers presented to her as an intermediary between Niki and Japanese parties.

Toward the Realization of Her Dream

“Yoko, come here.”

Led by Niki’s hand, Yoko walked through bushes at the Tarot Garden to reach the just completed 13-feet high sculpture, the Hierophant Tarot Card, No. 5. Three of the four pillars were covered with mosaic mirrors, sparkling and reflecting the surrounding greenery. A Chapel, Temperance Tarot Card, No. 14 was also completed. Everywhere Yoko looked, she found that the construction had progressed much further since her last visit.

Niki said, “I have something to show you,” and guided Yoko to a nearby large sculpture, the Tree of Life, which was not the motif of Major Arcana; it was crowned with branches of snake heads, slightly looking like Yamata no Orochi (Eight-forked serpent in Japanese mythology). The center of the trunk, the belly part of snake, was embedded with fifty tiles; each was a Niki’s illustration tile.

“These tiles are ceramic. The title is My Love. I’ve made two sets. One is here. The other is… for your museum,” Niki said shyly.

Yoko nearly jumped out of her skin.

“Oh, Niki! I don’t know how to thank you!”

My Love was a narrative from the beginning to the ending of love. It was quite a charming story.

“First of all, I need to find land for the museum,” Yoko said.

“You should find spacious land, far from Tokyo, where I’d be able to breathe clean air and stay a long time,” Niki replied.

Could I find such an ideal place? Yoko sighed. She envied Roger Nellens who owned a huge land in Belgium. But it took Niki a long time, too, to find and acquire this vast estate in Italy. I should be able to do the same.

“I’m going to create a maquette for your museum.”

Yoko’s voice shook with excitement. “How wonderful! Everybody in Japan will be surprised if we have a museum shaped like your work.”

“What matters most is whether you like it,” Niki said. Yoko felt very proud of herself.

“Let’s make a unique and beautiful museum!”

Niki and Yoko kept talking endlessly, happily and excitedly, aiming at the realization of their dream.

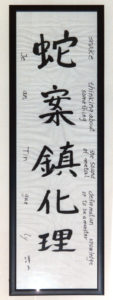

Ni Ki Do San Fu Aru (Seal in Kanji Chinese Characters)

Seal presented from Yoko to Niki.

“Jean Tinguely” in kanji written by Yoko.

“I designed a seal of your name in kanji (Chinese characters). Here it is.”

When Yoko visited Niki last time, she was given a snake bracelet. As a return gift, Yoko was giving Niki an original seal.

Niki had been deeply interested in the kanji. Kanji such as Seigi (Justice), Taiyo (Sun) and Tsuki (Moon) were engraved on paths of the Tarot Garden. Those works were based on the kanji Yoko had written on hanshi calligraphy paper with ink in the Tarot Garden. Yoko had taught Niki that every kanji has a meaning or two.

What Yoko had brought was nothing but unique. The body of the seal was modeled on Shakoki (goggle-eyed) Dogu (clay figurine) from the Johmon period (10,000 BC to 300 BC). It looked as majestic as Niki’s Nanas. It was made of silver. Yoko thought up the kanji engraved on seal; she turned “Niki de Saint Phalle” into a series of kanji.

(Translator’s note: Shakoki Dogu is a figurine of a plump woman. There are many theories on what those figurines were used for. One common theory is that they were a talisman for good health or safe childbirth. Another theory is that these were goddesses to whom the Johmon people prayed for food and health.)

“Some critics have spitefully speculated that your name Phalle was reminiscent of phallus and that’s why you had been creating those works, Niki. Actually, I find your name has very good meanings. When I apply kanji to the sound of your name, it would be Ni Ki Do San Fu Aru.”

Yoko wrote the name fluidly on hanshi paper, which she had brought from Japan.

“We say one means origin, two beginning, and three harmony. So, my interpretation of your name is this: Ni a beginning; Ki a tree; Do earth; San brilliant; Fu a wind; and Aru an existence. That symbolizes your art world, don’t you think?”

“Oh, Yoko! That’s really a mysterious story. I’m moved to hear that my name has such meanings. And I find lines of kanji very artistic.”

Then Niki added, “How do you write ‘Jean (Tinguely)’?” After pondering for a while with her arms folded, Yoko wrote “Ja An Chin Ge Ri” with ink on hanshi paper.

“A snake (ja) is reflecting (an) on a tree; (chin) is the sound of bell. It fits Tinguely’s works, too; (ge) means monster; and (ri) comes from richi, intelligence or reason.”

They shared a hearty laugh. Niki seemed to love Yoko’s kanji’ writing of “Ja An Chin Ge Ri.” The next time Yoko visited Niki’s studio, she noticed that it had been framed and hung on the wall.

→ Chapter 9. A Pile of Problems