*

Niki and Yoko

From a Shitamachi Okami to a Niki de Saint Phalle Collector

*

*

Written by Yuki Kuroiwa

Translated by Nasuka Nakajima

*

Chapter 3. The Elopement

The Encounter with Tsuji Masuda

“Do you happen to know any charming girl who may want to be my girlfriend?”

Tsuji Masuda asked cousin Chisato Aoki, who was a classmate of Shizue’s in her girls’ high school days. Tsuji was a Todai (University of Tokyo) student.

Let’s see, Tsuji likes the unique and outspoken type … AND one with good looks. Kuro may be perfect. Shizue’s face came to Chisato’s mind.

That weekend, Chisato headed to Children’s House in Ueno. As usual, many students were coming in and going out of the building. “Chisato, long time no see!” Shizue came running to her.

“How are you?” asked Chisato.

“I’m fine, but you’ve got to hear this! I just asked Watanabe, the Todai man, ‘Isn’t Für Elise a wonderful tune?’ What do you think he said? He said, ‘That’s not a classical piece.’ I wasn’t asking him such a thing. How square he is!” Shizue was fumed.

“True, true. By the way, Kuro, a cousin of mine is a part-time French instructor, and he’s been looking for some students. Didn’t you say you wanted to learn French?”

“Yes, I do. Is it okay if I bring along my friend Otani-san? She’s my roommate.”

“Sure. Then, next Wednesday, I’ll take my cousin to Tsuda.”

Shizue’s first impression of Tsuji was this: “though on the short side, he’s energetic and has a strong personality.” Unlike the intellectual type around Shizue with the tendency to discuss difficult topics, Tsuji struck her as a refreshing man who didn’t lose sleep over trivialities.

Tsuji’s optimistic, somewhat relaxed attitude stemmed from his experience immediately after the Great Tokyo Air Raid. In the ruins, he witnessed copious debris and a mountain of burnt dead bodies. “Once you saw that, you’ve seen everything,” felt Tsuji. And there was that feeling of liberation he savored even in the defeat of Japan. Feeling an uncontrollable urge to do something in Matsumoto where he had been evacuated, Tsuji jumped on the train bound for Shinjuku of Tokyo. There was no end if you started thinking pessimistically. He decided then that he’d “start living a happier, more enjoyable life.”

As soon as Tsuji returned to Tokyo, together with his friends, they jointly presented the play Cyrano de Bergerac as part of the school festival at a metropolitan high school. The play was given in the remaining Hall. Three months had passed after the war. Tsuji, whose father was an established Japanese-style painter, painted all the backgrounds of the stage himself. The play, based on the sense of freedom from the gloomy war and heartily expressing romanticism of humanity, turned out to be a big hit. Tsuji’s life motto was formed then: “Drama is the root of all arts, as well as the starting point of life energy.”

It’s only natural that Tsuji and Shizue were attracted to each other.

However, “teaching Shizue French” was just an excuse. Tsuji in later years admitted that he “never taught her French seriously.”

After a several dates, Tsuji said to Shizue, “I want to meet your father to approve our marriage.”

At first Shizue thought it was a joke. “I can’t cook; I’ve learned nothing about wifely duties,” said she. Tsuji responded nonchalantly, “Cooking, washing, and cleaning? No problem. I’ll do all that.” “With this person, life will be carefree,” Shizue thought.

Shizue was seventeen, and Tsuji twenty-two.

Shizue Visits Her Father

Shizue and Tsuji

From July through September every year, Arae stayed at the house of Aunt Kitagami and Keizo, who had decided to remain in Ueda after the war. One reason was to catch ayu sweetfish on the Chikuma River. It was fun, but also had a practical business purpose. In the evening, Arae sent to the Ueno Hanaya the ayu he had caught and wholesaled from professional anglers. The ayu dish was fresh and delicious, and thus, a very popular item at the Hanaya. When Arae was absent, a chef named Oizumi and the counter staff managed the restaurant.

That summer, Father was again in Ueda.

“Hello.”

After sunset there was a voice at the genkan entrance.

“Yes, I’m coming. Oh, my. Shizue-chan?!” said Aunt Kitagami, surprised. “What? What happened?”

There was another reason for her surprise. There was a young man with a smile behind Shizue.

“Auntie, this is Mister Tsuji Masuda.”

Father had been enjoying the fresh ayu he caught with a drink.

“Uh?” he said. But then his expression suddenly became stiff when he saw the second figure entering the house after Shizue.

“Father, this is Mister Tsuji Masuda. He’s a Todai student,” Shizue introduced him.

Tsuji with a tense expression said.

“I have been dating with your daughter. I’d like to marry her. Please approve our marriage.”

Arae dropped into the chair with a thud, and silently, without really looking at the two, folded his arms. Time passed. Arae looked as if no matter what Tsuji said to him, he could not hear anything. “I felt like I was talking to the air,” Tsuji thought.

After a while, Arae mumbled, “Masuda-kun, if you want to get married, how about waiting until you receive a salary?”

“I understand.”

Tsuji made a bow.

After Tsuji left the house to return to Tokyo alone, Shizue and Father were sitting down face to face. Clink-clink. the furin wind chime was tinkling. The summer was to about to come to an end.

Father said, “It’s too early for you to get married. You’re a student. Focus on your study. Don’t you forget the dream of becoming a Diet member.”

“No, I won’t.”

Shizue said, looking down. She, too, felt strongly that she must study for now in order to graduate from college.

Tsuji, sitting in the train on the way to Tokyo, was recalling the exchange with Arae. He considered it anew.

“I guess it’s not a bad idea to drop out and become a salaried worker.”

When he thought about it, the face of one classmate came to his mind.

“I should consult him.”

Tsuji and Seiji

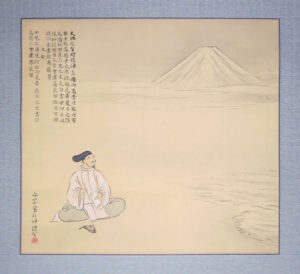

Tsuji’s father, Seiso Masuda’s artwork Yamabe no Akahito

The Masuda family in Setagaya, Tokyo, was also strongly opposed the marriage of Tsuji and Shizue.

“I didn’t send you to the University of Tokyo so that you can marry a daughter from a Shitamachi oden shop.”

Tsuji’s father, Kyutaro, was quite blunt.

(Translator’s note: oden is an inexpensive popular Japanese food, consisting of vegetables, fish dumplings, tofu and other ingredients stewed in a light, soy-flavored broth. Ueno Hanaya was a much more sophisticated restaurant than an oden shop.)

Tsuji Masuda was born in 1926, in Ichigaya-Tani-machi, Ushigome Ward of Tokyo. When he was little, he was involved in a traffic accident in front of his house. Since then his parents were worried about the location, and soon the family moved to Daita, Setagaya Ward, a suburb of Tokyo. The youngest of four siblings, Tsuji was doted on by his parents. His older brother, Seiichi, would eventually leave his mark on archaeology as a professor at Tsukuba University.

Tsuji’s father, Japanese-style painter, was born in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture. His pseudonym was Seiso. When Tsuji was a child, he was the leader of the neighborhood kids. His daily chore after school was to mix pigments and binder used for Japanese paintings in preparation for his father’s work.

After elementary school, Tsuji advanced to the Tenth Metropolitan Middle School (present-day Nishi Metropolitan High). His father was also there as an art teacher. One of the Japanese teachers there was the linguist Haruhiko Kindaichi [1913-2004]. Since teachers of this newly founded middle school often gathered at Masuda’s residence to discuss things, Tsuji knew them by sight before entering the school. Thus, the hard-nosed boy had no choice but to behave himself at school.

“A student named Tsutsumi will sit next to you. Look after him.”

Right after enrolling at the middle school, Tsuji was told this by the school principal. What happened was this: Tsuji was selected as the caretaker of Seiji Tsutsumi, a son of Yasujiro Tsutsumi [1889-1964], the founder of the Seibu Group, who had made a name for himself in political and business circles.

Seiji was a quiet young man, completely opposite to Tsuji who had to take action as soon as he had an idea. Seiji was the calm, level-headed type who considered things, one by one, logically. Though their personalities differed, they seemed to have hit it off well. They started hanging out often. Tsuji frequented the Tsutsumi residence in Hiroo. “Nice to see you,” Yasujiro was friendly to him. There was new exchange between the fathers as well. Yasujiro became a valued client for Kyutaro’s Japanese-style paintings.

After that, the two boys went separate ways, Tsuji to a Metropolitan High School, and Seiji to Seijo High. But the relationship remained unbroken. In fact, they would later be reunited at the University of Tokyo.

“If you want to get married, wait till you received a salary.”

After being told this by Arae, Tsuji, on his way back to Tokyo, was remembering Seiji. To be exact, he was thinking about getting a job from Seiji’s father, Yasujiro. Back in Tokyo, Tsuji consulted Seiji at once. He reported back immediately.

“Father says he can see you.”

Tsuji visited the familiar Hiroo residence for the first time in a long time. He used to come here often on a casual basis. But this day, he was a nervous wreck. Upon seeing Yasujiro in the living room, Tsuji bowed deeply. Slowly and timidly, he raised his face. The face that he thought was glaring at him with a frown, suddenly changed.

“Well, work hard, okay?”

Suddenly, all the tension dissipated. Tsuji almost fell to the floor. His knees were still shaken.

That’s how Tsuji, while being a Todai junior, joined Kokudo Keikaku Kogyo (Land Project and Industrial, Co., Ltd., now Kokudo), which was managed by Yasujiro Tsutsumi. His duties were mainly that of a student or errand boy, such as cleaning and gatekeeping. However, since Tsuji was always with Yasujiro, he was able to closely observe how this powerful entrepreneur conducted his business.

The Graduation

“What do you think? Is she coming?”

Female students in hakama (traditional divided skirt) were whispering to one another.

“She won’t. Never. Her expression showed no interest whatsoever.”

“I think so, too. I can bet on it.”

It was a spring day in 1951, the graduation day at Tsuda Juku. The consensus among Shizue’s friends was that she wouldn’t attend the ceremony. However, Shizue did appear, in western clothes.

“Kuro-chan came. Wow!” everybody was surprised.

Shizue was not like most other students who would automatically listen to their teachers, attend lectures, and study by rote to pass the exams. She read whatever she wanted to read and take action for herself. Oftentimes, she did not return to the dorm. She managed to receive passing grades, and focused her energy on theater and other things she really wanted to do. She joined the Social Study Group and discussed with fellow members such subjects as what role society should play in the future. Shizue had picked this college for one reason and that was to study English. However, before she truly had realized it, she had not been content with learning English-centered subjects only.

After graduation, Shizue was supposed to teach English at a middle school. Tsuji found employment to “receive a salary” as told by Arae. But Arae showed no sign to give consent to their marriage; he told Shizue, “You’ve been deceived by that man. A Todai man would never seriously consider you wife material.” Shizue, meanwhile, had been feeling, “I should learn a trade so that Father would approve our marriage.”

Once she decided to do something, she had to move forward. There was no time to lose. She wanted to work immediately. Shizue had a hard time controlling her impatience.

The Rookie Teacher

Shizue as a teacher (above right)

“Oh no! I’m so late!”

Shizue jumped out of bed. She quickly changed, grabbed her bag, and, without brushing hair, started running.

Shinobugaoka Metropolitan Girls’ High School, her alma mater, had become Shinobugaoka Metropolitan High School under the new school educational system. Shizue had been hired as English teacher at Horai Middle School in Taito Ward, which had been built as an annex.

The rookie teacher worked very hard. She took up a number of classes, and, after the regular classes, she also taught supplementary lessons. Around that time, Shizue had decided to study law. By day she was an English teacher; by night she attended the evening law class at Meiji University. When she got home, she often had to grade students’ exam answer sheets. After the late supper, it was already midnight. She constantly sprinted to school without breakfast.

It was fun teaching middle schoolers, and Shizue was an enthusiastic teacher. Every student seemed to listen attentively to her with twinkling eyes. Students looked up to her, “Kuroiwa Sensei, Kuroiwa Sensei.”

One day Shizue called out during the recess, “Those who want to do sumo wrestling, gather here!” Many students came.

“Hakke yoi nokotta, nokotta.” (the gyoji referee’s urging words to fight on).

Shizue called it sumo, but it was more like a pushing & shoving match. But the students were screaming in fun. That was Shizue’s idea to cherish physical contact with the students.

Even when the class bell rang, the students’ excitement didn’t cool down. A senior teacher approached Shizue.

“This is not good, Miss Kuroiwa. The term exam is coming. Please don’t let them play. Also, about A’s grade, which I told you the other day, since he is not in the High School-Prep class, give him a 2. And please give B a 4 since he’s going to advance to high school.”

The older teacher said this to her and walked into the Faculty Room. Shizue had given a 3 to both students. Those days, the grading system was called the five-grade relative evaluation. It meant that no matter how hard a student studied, his or her grade may not improve depending on the grades of other students. Shizue felt sorry for the students. The mother of B in the prep class frequently visited the school and curried favor from teachers. That was the way it was.

After the class, teachers supervised on a rotating basis students’ cleaning duties. They made sure that male students had buttoned all the way up. Students could not play or have much fun. Grade evaluation was ambiguous, yet the rules were kept rigorously. Shizue felt a rising anger toward the overly rigid educational system.

“Kuroiwa Sensei,” a voice said, and Shizue turned around. The school principal was standing there.

“How are you? Are you used to the school by now?” the round-faced principal smiled.

“Yes, completely,” said Shizue.

“Do you still go to Meiji University for the evening law class?”

She did. But Tsuji tagged along with her, worried, because “there are a bunch of men around her.” In reality, Shizue hadn’t had much progress in study.

“By the way, did you bring your lunch today?” asked the principal.

“Oh, I forgot.”

Shizue looked down, embarrassed. For days and days, she had skipped not only breakfast but also lunch. Before she knew it, she had lost a lot of weight. Just the other day, the principal was worried about her, and gave her some of his lunch.

“You may think you’re young, but if you continue to push yourself too hard, you’ll have to pay for it later,” advised the principle in a slightly harsh tone.

“Yes, I’ll be careful, sir.”

As soon as Shizue’s said so, she felt dizzy, and her mind went blank.

“Miss Kuroiwa. Are you all right? Help! We need help here!”

Shizue barely heard the principal’s shouting voice. Then, she lost consciousness.

The Elopement

When she awoke, she was lying on bed in a hospital. Arae was standing by her, scowling.

“Malnutrition, the doctor said,” muttered Arae.

Shizue was silent. By this time, their relationship had been only worsened. Every time they met, Arae would oppose her marriage to Tsuji. Shizue, too, felt angered by the incorrigibly stubborn attitude of her father.

Tsuji was working under Yasujiro Tsutsumi so that Arae would someday approve their marriage. Shizue was working, too, in high spirits as an English teacher. Yet, Father didn’t seem to budge. In addition to the hectic schedule, another reason Shizue lost a lot of weight was the constant strain of worry over that matter.

On top of that, Arae, who used to say, “Wait until you receive a salary,” nowadays said, “I can’t give my daughter to a man whose accomplishment is to just receive a salary.”

“My father came up with another reason to oppose our marriage,” Shizue told Tsuji when he visited her at the hospital.

“Receiving a salary isn’t good enough, he now says, even though that used to be the prerequisite.”

Shizue was angry. Tsuji, by contrast, said cheerfully after a long consideration of the matter.

“There’s some truth in what your father says. If I were a hobo, he would be worried. Receiving a small salary is not sufficient for a man. The point is that his son-in-law must have some gravitas. All right. Maybe I should return to the university and graduate from it.

Shizue looked at him anxiously.

“Even if you do it, Father would never accept our marriage, I can tell,” thought Shizue.

“In any case, don’t worry about it. What you need to do is eat a lot and be healthy again,” Tsuji said, and left.

Tsuji set foot on the Hongo campus of the University of Tokyo. He hadn’t been there in a long while.

He thought his name had been removed from the register, but the name was still there. He was advised that if he paid the appropriate tuition and completed the graduation thesis, he could graduate.

Tsuji agonized over quitting the job. He had asked Seiji to do him a big favor. Tsuji learned a lot from watching Yasujiro. After a long vacillation, however, he finally told Yasujiro, “Forgive me for being selfish, but I really would like to return to the university.”

“True, true. Study is important,” said Yasujiro simply.

“Good luck.”

Tsuji felt such a warm feeling as if Yasujiro was his own father.

In September of 1951, Tsuji reenrolled at the University of Tokyo. He tackled the graduation thesis on a furious pace, and then completed it.

Shizue was discharged from the hospital. She returned to work at school, but physically, she could not continue. She handed in her resignation. The principal urged her to change her mind, but she felt that if she continued, it would cause trouble for her students.

It was a short period of teaching experience to Shizue.

“Father, it looks like Tsuji-san can graduate from the university.”

The two went to Hanaya to report the news to Father. But Arae’s face remained grimaced

“No difference. I won’t approve!” yelled Arae abruptly.

He stood up and went to the back of the house. Shizue’s anger exploded. She yelled back at him.

“All right! If you don’t allow us, we’ll do it on our own!”

And thus, Shizue and Tsuji eloped.

The Young Couple

Shizue and Tsuji

They headed for Ueda City in Nagano Prefecture. Within Ueda, Aunt Kitagami and Keizo lived in Atago-machi, and Grandma Chiyo in Babancho.

“What happened?”

Keizo was surprised to see the two at the door.

“I left home because Father never approves of our marriage. We eloped, you know. Elopement. We crossed the Usui Pass on foot.”

“Eloped?!”

“Oh, my. This is serious,” Keizo thought. They went to Yokokawa by train on the Shin-etsu Main Line. Then, they went over the pass to Karuizawa on foot.

“On the way, land leeches fell on us. They stuck to our skin. It was terrible, wasn’t it? Tsu-chan,” said Shizue. But Keizo thought, “It doesn’t look so terrible at all. Shizue looks happy.”

“We bought the Kamameshi of the Pass (rice-and-chicken dish served in a small ceramic pot) in Yokokawa. That was very good, wasn’t it?” said Tsuji, equally happily.

“What are you going to do? Arae doesn’t know you eloped, doesn’t he?” asked Aunt Kitagawa.

“For the time being, we’ll stay at Grandma’s house. We won’t go back to Ueno,” Shizue replied in a strong tone.

“I have the university graduation ceremony to attend. I’ll find work in Tokyo as soon as possible. Once I find a place to live, I’ll call up Shizue and we’ll live together.”

Tsuji’s resolve was firm.

After the young couple left for Grandma Chiyo in Babancho, Aunt Kitagami telephoned the Ueno Hanaya.

“Arae? Big trouble. Shizue and Tsuji are here. She says she won’t go back to your place.”

“She’s no longer my daughter.”

Kitagami heard Arae’s irritated voice, and then the line went dead on the other side.

Oh no, what could happen now? The relationship between the stubborn two of a kind — Arae and Shizue — has deteriorated so badly now, there’s nothing we could do but to wait and see.

Aunt Kitagami and Keizo nodded to each other in mutual agreement.

Tsuji Finds Work

While Shizue stayed in Ueda, Tsuji returned to Tokyo. He wanted to find work quickly and start a new life. But, although he may be able to finish his graduation thesis in time, Tsuji had lagged behind on the job-hunting battle. Those days, employment exams started around September; Tsuji showed up at the Placement Office at the end of the year.

“There’s no chance if you come this late. Come March, there’s maybe an opening at some school,” the clerk was curt and unsympathetic.

Tsuji was about to give up, but realized that the life with Shizue was at stake. In early March, Tsuji visited the Metropolitan Government Office in search of teaching job. There was no opening. He was about to leave the room with a sigh when he heard a familiar voice.

“Hey, Masuda-kun. You’re Masuda, aren’t you?”

Tsuji turned around to find a middle-aged man, looking at him somewhat nostalgically.

“Huh? Sensei? What are you doing here?”

The man was Kiichiro Tanaka who taught Japanese at the Tenth Metropolitan Middle School. He had become the Personnel Section Chief at the Education Bureau of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

After Tsuji explained his situation to his former teacher, Tanaka gave him a grin.

“If you do as I say, things may work out for you.”

The opening for teaching job can happen quickly. Tanaka advised Tsuji that he commute to the Education Bureau.

“You should take seat in front of the Personnel Section so that I can call on you first thing when there’s an opening.”

After that, Tsuji commuted everyday to the section with his box lunch, sat in the deserted hallway between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. He didn’t want to miss out any opportunity; he even limited going to the restroom.

One day in late March, the Education Manager came running, his slippers flapping, from one end of the hallway. He opened the door to the Personnel Section and went inside. Tsuji had been sitting there every day for two weeks. His hunch said, “Go!” Tsuji quickly followed the Manager into the room.

“Mr. Masuda, good for you. It was worth waiting, wasn’t it?”

Tanaka, who was thumbing through the document the Manager had handed over, gave a big smile.

Tsuji became a social studies teacher for the night program of at the Fifth Metropolitan Commercial High School in Kunitachi City.

A New Life

Tsuji rented a room in Kunitachi City and called up Shizue. The room was on the second floor of a small single-family house. Due to the postwar housing boom, the Kunitachi population had soared. Everything felt fresh to Shizue who was used to living in Ueno.

One day, Nenko from girls’ school days visited Shizue in the new residence.

“Oh, Nenko! Thank you for coming, great! Today, it’s your treat!

“What?! My treat?”

Nenko’s eyes widened while Shizue called a soba noodle shop and ordered soba for two.

Every time a friend came to see her, Shizue’s had them treat to her without fail. Friends in need were friends indeed. Although Tsuji was working, their financial situation was in dire straits.

“You look fine, Kuro,” said Nenko.

“Yes. My health is back, thank God.” She had lost much weight due to malnutrition. By this time, however, she was almost back to her old weight.

“What do you do in the house all day?” Nenko asked.

When Tsuji decided to marry Shizue, he reassured her by saying, “I’ll do all that, cooking, washing and cleaning.”

“Listen! I said the other day to Tsuji, ‘Well, please do household chores — cooking, washing and cleaning, okay?’ What do you think he said? ‘What? Did you seriously believe I’d do all that?’ he deadpanned. So, I’ve been doing all the duties,” fumed Shizue.

Shizue grew up hearing her father say, “Cooking is for men.” She also did very little washing and cleaning. That’s why she was counting on Tsuji, only to hear him say, “You took my words seriously?” After that, Shizue began to call Tsuji “Bigmouth Tsuji.”

Shizue had no choice but to reluctantly do domestic chores. She first tried cooking, but all she remembered was the images of cooks at Hanaya. She poured shoyu soy sauce from an industrial-size bottle into a cylindrical pot, glug, glug, plug, and then, flipped in two slices of fish. She cooked them to a rolling boil. The result was, sure enough, too salty to eat. Nevertheless, Tsuji ate it without saying a word.

“Is your father at Hanaya still against the marriage?” asked Nenko anxiously.

“Ha! I have no clue. Haven’t seen him since we left home. But according to Shi-chan at Hanaya, who kindly and secretly brought us some mochi (rice cake) and miso (soy bean paste), Father seems to be in a bad mood.”

“Don’t you work, Kuro?”

“Not for a while. But I’ve been teaching English to some of the evening class students Tsuji teaches at the Fifth Commercial High School. I teach only those who want to advance to college. When the class is over, Tsuji brings them here. After the English class, I sometimes serve late night meals. We went to the movies the other Sunday night with those students.”

Shizue sounded happy.

“Oh, yes. I was asked to write a culture column for the newspaper of the Labor Union Youth/Women’s Group. I think I’ll try it for starters,” said Shizue. It was a request from the Labor Union that Tsuji and Tsuji’s fellow teachers belonged to.

Then, Tsuji came home, “I’m home.”

“Oh, Nenko-chan, Glad you came,” welcomed Tsuji.

“Hello, Tsuji.”

Nenko looked at the faces of Shizue and Tsuji. They looked quite lively. “Their new life must be fulfilling,” thought Nenko.

“Nenko, is it okay to make three orders of soba noodle?” said Shizue promptly.

Separate Activities

At that time, many young people who had experienced Japan’s defeat of war were sympathetic to the left wing movement. Shizue was now in charge of writing a column for the newspaper of the Labor Union Youth/Women’s Group. She wrote articles after interviewing people involved with various types of activity. The experience was very different from writing plays during her college years. But it was fun. Though she earned no salary, she received several books as a token of gratitude.

One day, Shizue covered the meeting of a Communist Party affiliate. Its activities included protecting children by driving out harmful kami-shibai picture-story shows, and by creating educational picture shows. Picture shows those days enjoyed a great popularity among children in Japan. On the other hand, radical expressions were used to draw attention in some shows, which became increasingly problematic. Many of the kami-shibai storytellers were war veterans; those workers had no choice but to scrape along by showing picture-story shows. The members of this particular group created shows appropriate for educating children, and then advertised them on foot by taking a puppet show and a musical band to each of kami-shibai on site under the catchphrase, “Come see this man’s picture-story shows. Something interesting will happen.” Shizue fell in love with this group’s activity.

In the meantime, the union newspaper got in trouble, and the office was closed.

“Please. I’d like to work here,” Shizue desperately pleaded to A., the central figure of the picture show group.

“That’s okay, but we cannot give you any salary,” said A.

“I don’t need any salary. I’ll commute with my bento box lunch.”

From the next day, Shizue began to work for the group. Work included wrapping hard candies, and cutting vinegared seaweed with scissors. When everybody else returned from the live kami-shibai performance (called “Bai”), Shizue joined the practice. To her, those activities with people with common goals were so much fun.

When Shizue came home from the picture-story show group, Tsuji, in turn, left for high school. Social studies covered wide-ranging subjects from Japanese history, world history, economics, ethics, and geography. Tsuji believed, “In social studies, it’s not enough to just learn by rote. One needs to fully comprehend what’s at the root of each event as well as the zeitgeist of the period.”

Tsuji loved to talk. He talked fast like a stand-up comic by digressing to his favorite genres such as art theory, philosophy, and theology. Those who were taking a nap, tired from daytime work, would be awake and be drawn to Tsuji’s talk. His students called him “Massan,” not “Masuda Sensei,” and looked up to him.

One month into his duty as a teacher in 1952, a group of demonstrators and police squads clashed in the Palace Plaza; the “Bloody May Day Incident” occurred. The size of the demonstrators swelled to 6,000 in number, and had a head-on collision against 5,000 policemen in front of the Niju Bridge, the entrance bridge to the Imperial Palace. Police shot at the demonstrators, resulting in one fatality. By this time, Tsuji had joined a local Communist Party branch and at the time of the incident, he was one of the participants in demonstration. Tsuji, however, could do nothing but to stare, dumbfounded, at what was happening. “A crazy, terrible thing just happened.”

Next day, when Tsuji went to work, a number of students had bandages. He guessed that they had been injured in the demonstration. Many among the evening class students worked at heavy industrial factories around Kunitachi City. They worked from early morning to evening and then studied at night, weary and tired bodies notwithstanding. They were indeed hardcore laborers.

After this incident, Tsuji became acutely aware that as a fellow worker, he could not conduct classes in an irresponsible manner.

The Secret

One day, there was a telephone call to Shizue. “I need to consult you.” It was from Seiji Tsutsumi.

Before Tsuji and Shizue eloped, Tsuji had introduced Shizue to Seiji, “This is my bride-to-be, Miss Shizue Kuroiwa.” After graduating from the University of Tokyo, they had kept a close friendship.

The gist of what Seiji said was this: “We’re in a desperate need for a place to mimeograph secret messages in correspondence. Can we use your living space during the daytime?” At that time Seiji was devoting himself to the Communist movement.

“Of course, but the landlady lives downstairs. And she has a daytime gathering of neighborhood ladies to sew kimono, which will be delivered to Mitsukoshi Department Store. Be careful not to be reported to the police.”

Those days, the Communist movement was subject to suppression by the police.

From the next day, three men whom Shizue called “bizarre-looking” began to come and mimeograph secret messages. Since the communal lavatory was located downstairs, when they needed to go, they had their ink-smeared hands in their pockets to avoid suspicion. Soon, however, the leery housewives began to talk in whispers.

“Masuda-san, do you have a minute?”

When Shizue came home from the kami-shibai show group, the landlady stopped her.

“These men, are they doing something during the daytime?”

“They’re my husband’s fellow teachers. They’re gathered to discuss a collection of literature compositions.”

Shizue replied nervously. But she knew she had to do something right away. The solution she came up was the portable potty. If they never go to the lavatory during the day, they wouldn’t be seen by the housewives. Thus, with the potty in her hands, Shizue tiptoed to the lavatory, passing the room where the ladies were sewing. It was terribly thrilling!

Later, she heard people say that the reason why Seiji asked her to keep this “secret” was because he had absolute trust in Tsuji.

In the meantime, Shizue, actively participating in the picture-story show group, soon began to question the way the central figure, A, conducted himself. A was equally skilled in puppeteering techniques, singing, and acting. He could quickly capture children’s hearts. Man with wonderful talents. He was also very self-centered in everything. He would say, “I’ve been shouldering the Communist Party. All you have to do is do as I say for the future of Japan.”

One day A said, “Today, we’ll have a meeting of criticisms.”

“Let’s self-criticize and mutually criticize each other.”

Everybody sat down on the tatami floor in a circle. When Shizue’s turn came, she didn’t mince words about her feelings toward A. A grew red in the face, enraged. He grabbed a large pair of dressmaker’s shears and stabbed it into the tatami, yelling, “You’ve been hiding those feelings from me till now?!”

The meeting turned into a major fight. After that day, Shizue stopped going to the kami-shibai picture-story show group.

Gathering Around a Nabe Hot Pot Dish

-1-300x223.jpg)

Arae in front of Ueno Hanaya

At around this time, Shizue’s father, Arae, was busy as a chef. Shortly before, he had opened the Ginza Hanaya on the street by the side of Matsuya Department Store. Although the building looked the same as that of the Ueno Hanaya, the signature menu items were inexpensive ones such as “Katsu (pork cutlet) Set Meal” and “Oden Set Meal.” Near noon, salaried workers in the neighborhood swarmed to Hanaya. There was also an off-track betting shop nearby. On Saturdays and Sundays, a great deal of its customers flowed into the restaurant.

One day stout Arae was pacing up and down, sluggishly like a bear, inside the Ueno Hanaya. He had both his hands behind his back, slightly leaning forward, and mumbling something. That was his habit when he was lost in thought.

“What’s happening with Boss?”

Chef Oizumi asked the counter lady.

“It’s all about Shizue-chan. That girl did it again,” said she.

Shi-chan said, “It’s been three years since Shizue eloped, right? She mailed the postcard, saying, ‘We got married even though we received no parental consent,’ to her relatives who had no clue whatsoever.”

“And so, those relatives got angry at her because she had humiliated her father. Boss is in a bind right now. Everybody is asking him, ‘What’s happening?’”

Arae and his father, Yoshitaro, were both cooks. Shizue’s mother, Chiyoko, married into Arae’s family from a family that also ran a restaurant in Jimbocho. His children are all girls. Although Arae often encouraged Shizue to ‘become a Diet member,’ deep down, he seemed to wish that his eldest daughter succeed the family business of managing Hanaya. “Hope she will marry a skilled chef.” But, the quintessential man of few words, Arae never talked like that, of course.

And then, Shizue told him that she wanted to marry a Yamanote uptown-grown son of a Japanese-style painter. On top of that, he was an elite Todai graduate. Such a man, in Arae’s opinion, would never be able to get along with artisan-thinking cooks because of strict vertical relationships. Yet, oblivious to Father’s feelings, Shizue decided to elope with that man.

[Translator’s note: Yamanote (“uptown”) is the hilly residential section of Tokyo. The residents in Yamanote tend to have greater individualism and privacy than those in Shitamachi. The term Yamanote indicates a higher social status than that of Shitamachi.]

(From left) Arae, Chiyo, Miyoshi, Chieko, Shizue and Tsuji around the nabe pot

More than three years passed. Shizue was virtually disowned by Arae. Arae thought that the relationship of the newly-wed couple would soon grow sour and Shizue would return home. But there was no sign of that.

“Why, now? Why did she have to notify their marriage to our relatives?”

Arae continued to pace up and down inside the restaurant.

Shizue, meanwhile, was staying at the Kitagami family in Ueda. She was four months pregnant. During this stay, Shizue characteristically utilized a unique idea of hers.

Shizue offered Keizo of the Kitagami family, who was studying for college entrance exam, to live in Shizue’s residence in Kunitachi in Tokyo, while Shizue would rent the vacant room. Experiencing her first pregnancy, Shizue was feeling anxious and helpless. But here with her aunt and Grandma Chiyo, she felt safe and reassured. Keizo readily agreed to the offer, saying, ‘This is very you, Shizue-chan.”

Shizue thought of her father, “The baby will be born. I can’t leave our relationship like this.”

“Aha! I got a good idea!”

That idea was to notify her relatives and the Hanaya staff by postcard of her marriage.

“This way, Father won’t be able to do nothing. No doubt about it.”

Shizue was right. Shortly after, Father called her. And for the first time in three years, Shizue and Tsuji crossed the threshold of Hanaya.

“Father, I’m expecting,” said Shizue.

After a long silence, Arae said, “I see … We need to have a wedding reception.”

Father finally gave the consent. He did it perhaps, aside from Tsuji, for the soon-to-be-born grandchild.

On the eve of the reception, Father, Grandmother, Shizue and her sisters, and Tsuji all gathered around a nabe hot pot dish. As a family they congratulated and celebrated Shizue and Tsuji’s new adventure in life.

Shizue later recalled this occasion. “There were at least six smiling faces over the steam of the nabe pot.” The most difficult period in Shizue’s life awaited after this.

Shizue was twenty-four years old. The pregnant bride somehow managed to wear a kimono costume. With a traditional Japanese-style hairdo, she made a cute bride, looking like a doll. They decided to avoid the wedding ceremony, but the reception was held in a zashiki room of the main Hanaya in Ningyocho. The matchmaker was chef-owner Tohei Okawa of the head Hanaya. Shizue’s relatives and several college friends from Tsuda Juku, and Seiji Tsutsumi were also in attendance.

Unlike the Ueno Hanaya, this Hanaya in Ningyocho was a large restaurant with several Japanese-style zashiki rooms. The dinner in the lacquered footed tray was quite exquisite.

From the perspective of those who did not know the family situation, it was what we call a “shotgun wedding.” It was also a very quiet reception. Still, Shizue knew deep down that Father did not approve their marriage wholeheartedly.

Shizue in bridal kimono costume

→ Chapter 4. You’ve Become Boring, You Know.