*

Niki and Yoko

From a Shitamachi Okami to a Niki de Saint Phalle Collector

*

*

Written by Yuki Kuroiwa

Translated by Nasuka Nakajima

*

Chapter 4. You’ve Become Boring, You Know.

Shizue Becomes a Mother

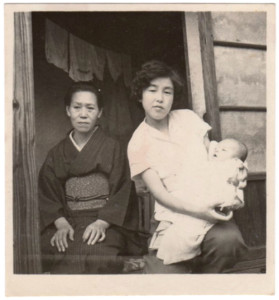

Shizue with her first son and Grandmother Chiyo

In August of 1955, Shizue had her first son, Daisuke. He was a bouncing, healthy baby boy. It also brought Arae great joy.

However, Shizue felt at a loss as a mother. She had managed domestic chores since she eloped. Still neither cooking nor cleaning was her forte. Now, child care was added to the to-do list. Her mother passed away when she was nine; she had no clue about the day-to-day care of a baby. She had to take care of the baby, holding a baby care book in one hand.Tsuji, meanwhile, never took part in child-rearing.

And then, there was one thing Shizue had been troubled by lately. She had begun to recall all the memories of her mother, Chiyoko, which had been sealed off her mind up to this point. Shizue and Mother never got along well. Thus, those memories were difficult to digest.

Those days, Shizue wrote down a lot of memories of Mother. Though written in form of novel, it depicted sad experiences of her own. The content was for the most part dark; it included a young child locked up in a small storage space under the kitchen floor, or a child, hurt from being scolded by her mother, roaming the busy areas of town. Shizue was keenly aware that she was the daughter of the mother who had given her all those difficult times in childhood. She was writing those sentences in order to acknowledge them and then affirm herself.

Around that time, at the suggestion of Tsuji, the “Life Drawing Workshop” started at night in the studio of Japanese-style painter Tamotsu Sato [1919 – 2004], who lived in their neighborhood. This helped the childcare-weary Shizue cheer up. She was also fortunate to learn that Mrs. Sato, Mikiko, happened to be a Tsuda Juku sempai (senior alumna). Occasionally Shizue participated in the workshop after lulling her baby to sleep.

“Good evening.”

Tsuji and Shizue, closely together, came into the studio.

“Oh? Where’s the baby?” Mikiko asked.

“We’ve left him at home,” answered Tsuji.

“It’s all right. He was sound asleep.” Mikiko’s eyes widened.

After drawing, Shizue could enjoy talking with other members. To Shizue, the workshop was the only breather she could take.

No Future Outlook in Sight

After the wedding reception, Shizue and Tsuji talked about having their own house. The rented Kunitachi rooms were cold and damp, not suitable to bring up children. While taking care of the baby, Shizue taught English to the neighborhood children. She wanted to help save as much money as possible for the new house.

In 1958, three years after Daisuke was born, they purchased a long-cherished house of their own in Sakuradai, Nerima Ward and moved there. The house looked more like a shanty building, but they were happy. Sakuradai at that time was mostly dry farmland as far as the eye could see. From the roof of their house, they could see the Sakuradai Station, a five-minute walk away.

The same year, the second son, Masashi, was born. He was a charming baby boy, especially when he smiled. Shizue did the best she could do as a mother. But day after day she was changing and washing diapers, and preparing meals three times a day; the only ones she could talk to were her young children. Tsuji would come home late at night, tired. And then she would jump out of bed, awaken by a crying baby.

What will become of me if I keep living like this? What should I do? What do I want to do?

In postwar Japan, students, thinking to the future, studied hard and debated passionately with high hopes and ideals to change Japan for the better. Shizue, too, had been one of them and took pride in it. That was why she had wanted to go out into the world quickly and realize her ideals. In reality, Shizue had met Tsuji and had eloped with him. After marriage, she joined the labor union newspaper and kami-shibai picture-story show group. She was hoping that those activities would provide her with some future outlook. They didn’t. She scratched the surface of various ideologies of the time, including Communism and existentialism, but none of them helped instill a sense of hope in her. Every day, Tsuji and Shizue were just busy making ends meet. Living from hand to mouth seemed to be all they could do.

Thus, the child-rearing duty was another contributing factor blocking the future outlook Shizue was so desperately seeking.

Father’s Illness

As of 1959 Arae led Jomata-Hogi-kai (an association of professional chefs) as its president, and the same year, he and his apprentices were assigned for the Japanese cuisine category for five days of the wedding of the then Crown Prince. For this achievement, he was later awarded the Shiju Ho Sho (Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon). In his early days, Arae had learned the Shijo-ryu Hocho-shiki, a ritualized style of filleting fish, which harked back to the Heian period [794 – 1185] in Japanese culinary school. He introduced knife rituals dressed in eboshi headgear and a flowing robe for Shinto events and on celebratory occasions. It was a traditional technique by which fish on the cutting board is handled with chopsticks and a kitchen knife only without ever touching it with the hands. The technique required both skill and courage. To be able to demonstrate it was an honor to any professional chef. Arae also appeared in TV cooking shows. He was fairly well known in the industry.

(Translator’s note: the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon is given to those who have made important contributions in academic fields, arts and sports.)

Arae had suffered from a severe case of gout and had been in and out of hospital. The primary cause was, as expected, his dietary habits. Typically, he followed the restrictions to his diet at the hospital, became better and was discharged, only to have to come back later after eating what he was not supposed to eat. This way, Arae could not sever the relationship with hospital. Worried, Shizue often showed up at Hanaya.

“Dad, you must be resting. You were just discharged.” “Heck, I’m in the middle of work. Go home, go home,” said Father, turning a cold shoulder.

Shizue thought hard to come up with a way to appear at Hanaya more casually. She decided to go there under the pretense of collecting the pay-phone money. Once a week, she turned up at Hanaya both in Ueno and Ginza. Few among the staff members, though, welcomed her in a friendly manner because of her notorious elopement. They seemed to feel that the eloped, cash-strapped daughter was there because she counted on the public phone fee.

Into the Devil’s Den

Tsuji was good at flattering people. “What a waste of a talent! A gifted woman such as you not working!” said Tsuji to Shizue continuously. Later, Shizue confided to a close friend, “In a sense, he had foresight.”

In 1960, the protests against the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty rocked Japan. At about the same time, Japan entered an era of high economic growth. Tsuji taught the evening class at high school for eight years. During that time, both the students and the perception of ideal education changed greatly. By 1960, Tsuji was teaching at two schools in Kunitachi City and Itabashi Ward. He had gradually realized, though, that teaching was not his calling.

Just then, there was talk that Hanaya was going to open a shop in Seibu Department Store. Seiji Tsutsumi was already the store manager of the Ikebukuro Seibu Department Store. Seiji had set the condition that Mr. and Mrs. Masuda (Tsuji and Shizue) be involved in the management of the shop.

Tsuji showed much interest in it. But Shizue strongly opposed it. To her, it was utterly unthinkable that a total novice like Tsuji going into a business, particularly the Japanese-style restaurant business where peculiar traditional customs died hard. On top of that, Arae, her father, headed an association of professional chefs, which complicated the situation. In Shizue’s mind, the restaurant business appeared to be the devil’s den.

However, Tsuji, an eternal optimist, accepted the offer easily, saying, “Things will work out.”

Arae showed a sour face. He, too, was thinking that Tsuji would never make it. Still, opening a shop in a department store was a very attractive idea. And since it was Seiji who made the condition to include Tsuji, Arae had no choice but to agree to the offer.

Tsuji’s work began at the Ikebukuro Seibu Department Store. The delicatessen in the basement floor sold everyday side dishes cooked at the Ueno Hanaya. The shop had two showcases. Tsuji was in charge of sales. Every day, Tsuji left home in the morning with two bento lunch boxes. During the day, he sold food at the deli; at night, he taught in Kunitachi and Itabashi.

Shizue, a little concerned about Tsuji, went to the department store without telling him. Piggybacking the younger son and holding the hand of the older son, she had a sneak peek at the shopping space from behind a pillar.

“Thank you so very much!”

Tsuji in a white coat deeply bowed to a customer. Looking at this sight, Shizue felt like crying.

After a time, Seiji summoned Shizue.

“I’m thinking about removing the side-dish deli section, and in its place, having Hanaya in the seventh-floor Variety Restaurant space. And by the way, Shizue-san, isn’t it about time you also worked?”

Shizue was taken aback.

“Our children are still small…”

“You need to experience actual battle, you know.” Seiji was persuasive.

Tsuji quickly agreed to the idea, “Yes, why don’t you work?” Finally, Shizue ended up working at the Ueno Hanaya. She had never thought that she would find her way into the devil’s den.

Variety Restaurant Floor in the Department Store

Tsuji quit teaching and became the manager of Hanaya, part of the seventh-floor Variety Restaurant in Ikebukuro Seibu. The title of manager was quite nominal; Tsuji had no control over the cooking, and the front counter was managed by a cousin of Arae. Tsuji had no say in either management or culinary matters.

In the world of restaurant business, those without ability are treated harshly. Arae never softened the strict attitude toward Tsuji, “Your status is below the cook.” Those days, feeding a family of four required at least a monthly salary of 40,000 yen. Tsuji’s salary was 30,000 yen. In Arae’s defense, his intention was based on this expectation: “If you put someone to hard work, he will grow in equal parts.” Still, Tsuji was put in an increasingly difficult position.

Shizue started working at the Ueno Hanaya while leaving her small children at home. All she could do were odd jobs such as dishwashing. To the staff of Hanaya, Shizue, the daughter of their employer, was a constant hindrance. Arae never treated her with favor. Shizue worked from morning till the closing time. After cleanup and the preparation for the next day, work time reached into midnight. Every day Shizue was exhausted. And when she got home, domestic chores and childcare awaited her.

One day, when Shizue got home, tired, Tsuji was already home, angry. He said that he had a quarrel with Arae. Something like this began to happen repeatedly.

Arae was increasingly fed up with the work at the department store. In his opinion, artisans should always try to cook good food even if disregarding the cost. He could not compromise in moderation in order to make profits. His mentality was not suited to the department store business in which the cost rate was a crucial factor.

Tsuji was also fed up. There was no work for him at the restaurant. He disappeared abruptly. The destination was almost always the pachinko parlor. That was why when Arae came to the restaurant, Tsuji was seldom there. After work, Tsuji was supposed to drop by the Ueno Hanaya. When he did, Arae yelled at him, “Where the heck have you been today?!”

When Tsuji grew up, he had never been scolded by anybody. Thus, this was an unbearable experience for him. When he got home, he shouted, “Your old man is crazy!” More and more, Tsuji drank and behaved violently.

No Way Out

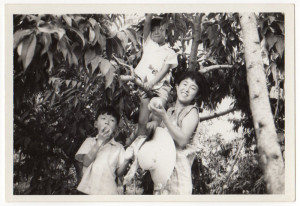

Shizue and her children picking peaches in Ueda

Hanaya also opened another shop inside the Seibu Department Store in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture. The staff became busy at a hectic pace.

At Hanaya, Tsuji was treated pretty much like a son who married into his wife’s family. Despite that, Tsuji alienated the staff by calling older cooks without the “-san” honorific and humming Russian folk songs. Needless to say, in strict vertical relationships, his behavior was frowned upon as lacking common sense and courtesy. They shunned him. Yet, Tsuji himself had no idea as to why they loathed him so much. That nonchalance deteriorated the relationship with them, cornering him further and further.

In the meantime, Shizue also had been frowned by the staff; she was given only miscellaneous chores. She worked all day long with no rest — at Hanaya and at home. In addition, Tsuji and Arae were on bad terms. Her anxiety never ceased. The melancholy finally developed into deep depression. Shizue saw a psychiatrist, an acquaintance of Arae’s. The doctor told her, “Your present condition is not too bad, but since you’re definitely overworked, you need plenty of rest and sleep.”

“Don’t exert yourself too much. Come back when you become healthy enough to work,” said Arae.

Shizue left Hanaya and started to trudge her way home through the Ameyoko alley, looking down slightly.

“I don’t do anything properly. Every time I try at something, my body screams. Whether it’s work or childcare or wifely duties, I’m only half good.”

Just then, something caught her eyes. It was the “Fortunetelling” sign at the entrance to a multi-tenant building. Her eyes and the fortuneteller’s eyes met. Shizue stood weakly before the teller.

“Right now you feel boxed in on all sides; everything seems to be against you,” said the fortuneteller.

“What do you think I do?”

“Don’t rush it. Don’t be desperate.”

After that, Shizue was able to shift her emotional gears.

She wanted to take advantage of this long-awaited opportunity. She decided to play a lot with her children who must had felt very lonely. They played the piano together and invited neighborhood kids to their house. On Sundays they went to the Seibu Ice Skating Center in Ikebukuro.

Tsuji was also leading an emotionally rough, frustrated life. Yet, by force of circumstances, he could not commit himself to saying, “I quit” to Arae. He didn’t want to admit his defeat. However, he could no longer stand the pressure; the time had finally come to say it. Upon hearing it, Shizue agreed with him, “That’s a good idea,” as if she had been waiting for it.

M Company

Tsuji decided to quit Hanaya. He reported it to Seiji Tsutsumi, and once again, asked Seiji’s father, Yasujiro, to find work for him. In 1961, Tsuji, at the age of 35, joined the Seibu Department Store.

“You need to learn sales again from the very basics,” Seiji said and found him a kacho section chief position at M Company, a food wholesaler that had been bought out by the Seibu Department Store. However, Tsuji could not feel at ease with this arrangement. He was going straight to the kacho chair by leapfrogging the hae-nuki (hired directly upon graduation) employees. Tsuji knew neither the account book nor food. His subordinates from those days recalled that Tsuji as a superior was always frowning or on the edge, thus virtually unapproachable.

Tsuji began to study bookkeeping with a help from a former fellow teacher at the high-school evening programs. He studied frantically since he could not afford to ask his subordinates even if he had questions.

At that time, the distribution system was going through a major change in Japan. Supermarkets began to pop up here and there, almost everywhere. One after another, private concerns went bankrupt because of it. Many among M Company’s clients were family-owned operations. Increasingly, they changed their business or quit. There were some cases of calculated bankruptcy, involving organized groups of gangsters. By standing up to them, Tsuji developed thick skin to troubling situations.

One day, Tsuji came home near dawn, exhausted.

“Why so late?” asked Shizue.

“We seized goods from a client in Kiryu, Gunma Prefecture, today.” said Tsuji.

“A bunch of us marched into a client’s shop where the family was living in a frugal manner. The head of the family clung to us, saying, ‘Please don’t take these goods. We’ll have nothing at all to eat from tomorrow.’ I brushed off his hands. It’s really tough. I don’t want to do this job anymore.”

It was rare to hear Tsuji complain.

Zoo in the Rain

“He’s late tonight, again.”

Shizue, while folding washed clothes, looked up at the clock. The date was about to change. At that instant, Tsuji stomped into the house. “Okaeri-nasai (Welcome home),” said Shizue. Ignoring it, Tsuji with an angry expression kicked about the folded clothes, and then slumped to the tatami floor with a thud.

He’s in a bad mood today, again. Shizue felt sad while staring at the scattered clothes. She used to be offended by such behavior of Tsuji. But now she was too tired or sad to be mad at the repeated act of venting his anger.

After working at Hanaya, when things didn’t work out for Tsuji, he quit it and moved on to M Company. But he was stressed out more and more. On top of that, he took it out on Shizue at home.

“Hey, now that you’re healthy again, I think it’s time for you to start working,” said Tsuji one day.

“Yes, that’s true. But what about the children?”

“Just hire a helper to look after them,” answered Tsuji. And then he added something that shocked Shizue greatly. The tone of the voice was strong.

“You know, a happy family sitting together — that’s just a corruption of humanity. You’ve become boring, you know.”

That night, Shizue could not sleep.

Several days later, Shizue, with her children and their house cat, set out to visit Miyoshi, her youngest sister, and her family home.

“Miyo-chan, can you take care of our cat for a while?”

“Sure. But what’s up?” asked Miyoshi.

“I think I’ll divorce Tsuji. So from now on, I may take our kids to Chieko’s place for a change of scenery.”

By that time, Chieko, her middle sister, had a family of her own in Kyoto.

The trip to Kyoto was a sheer disaster. It was the Christmas holiday season, cold and rainy. The train was congested. What was worse, they took seats in one of the rear cars. Near noontime, the children began to whine, “I’m hungry!” But the food-and-beverage cart never made it to their car. They missed the lunch. Even after arriving in Kyoto, Shizue learned that her sister wasn’t home. She didn’t know what to do.

“Mom, I’m tired,” complained Daisuke, the older boy.

“I know. Aunt Chieko isn’t home. What shall we do? Oh, I have an idea — how about going to the zoo?”

“The zo-o-o, the zo-o-o!” Masashi, the younger one, still lisping, got excited.

The rainy zoo was totally deserted. Shizue felt more and more gloomy.

“Why did I marry such a man? I shouldn’t have got married.”

Feeling blue and looking downward, suddenly, Shizue heard Masashi screaming, “Aaaaugh!” Turning his way, she saw him crying in front of the lion cage.

“What happened?!” Shizue sprinted to him and asked him. To her surprise, Masashi said that the lion had peed on him. Shizue burst into laughter in spite of herself, which then triggered contagious laughter from the boys.

After a while, Shizue heard Masashi scream again. This time, he was scratched by a monkey. There was a clear triple-scratch mark on his face. She felt sorry for Masashi, but had a good, hearty laugh. Despite being drenched, in the end, Shizue was in a better mood.

The mother said to the boys, “Shall we go home?”

Back in Tokyo, Shizue went to Miyoshi’s home. She told her that Tsuji had come and picked up the cat.

“Tsuji-san looked really troubled. ‘If contacted, tell her to come home as soon as possible,’ he said.”

The boys were sound asleep, totally worn out after the trip to Kyoto. Seeing those sleeping faces, Shizue decided to go home, for the time being.

Le Rouge et le Noir

Shizue continued to be in a depressed mood. Always struggling between ideal and reality, her characteristic positive quality had disappeared. She eloped, became ill, and every time she worked outside home, she felt defeated. As a result, she lost self-confidence in almost every aspect. Before she realized it, she was walking with her head down when in town.

In the early 1960’s in Japan when there were fewer stores, shoppers flocked to greengrocers at dusk. Shizue wanted to make some purchase, too, but could not gather enough courage to say, “I’ll take this, please.” Pushy housewives always got their way. With a shopping basket in one hand, Shizue remained standing before the greengrocer, staring at vegetables.

She could not quite make up her mind about divorcing Tsuji.

One good distraction for Shizue was, once again, reading. A lifelong book lover, she could never let go of books even after marriage. She read while putting a sock on her child; if the boy had thrown the sock away, she would retrieve it and put it on again while reading. She didn’t mind doing it again and again.

Shizue read a novel one day and it left a major impact on her. The book was Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black) by Stendhal [1783 – 1842].

How should I be as an individual? How should I live my life? When asked herself those questions, the words Arae used to say came to her mind.

“Girls, too, should be ambitious for the future.”

Shizue felt she should “strive to be ambitious.” In Le Rouge et le Noir, human ambitions are presented in a symbolic manner. It’s a novel about ambitious figures, whether men or women. At first, Shizue thought about writing her version of Le Rouge et le Noir with a female protagonist. Then it dawned on her that it would be faster and more interesting for her to behave like Julien Sorel, the protagonist of the novel as if being the heroine in her own life. After all, Stanislavski taught that once you determine the clear motivation, a life will be breathed into the action itself …

Le Rouge et le Noir became Shizue’s life compass. After that, she re-read the novel every summer.

A Thirteen-Year-Old Me

Shizue’s mind was made up. She would devote herself to implementing her ambitions. To do that, she could not afford to feel depressed. “I need to change,” thought Shizue. Then what should she be? Looking back on her life, she recalled the years when she was full of life. Instinctively, the “age thirteen” emerged in her head. Those days she feared no failure and had a mighty healthy curiosity.

“All right. I’m returning to the thirteen-year-old me.”

Once deciding this, mysteriously, she began to see the image of an ideal self. She felt the revival of the spirit that she used to possess when she was fearless. It was what we now call image training. People may wonder, “Why age thirteen?” But it was quite easy for her to believe such inspiration and put it into action. Thanks to that, she seized an opportunity to rediscover herself and start thinking positively.

Next, in order to realize one’s ambitions, she must have income. Virginia Woolf [1882-1941], one of Shizue’s favorite writers, once said in effect, “A woman must have money and a room of her own.” To be independent, first, she must earn money for herself.

(Translator’s note: Virginia Woolf actually wrote, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,” in her essay, A Room of One’s Own.)

One day, while Shizue was reading the newspaper, she saw a quote of a certain powerful politician: “What is politics? It means to generate something from nothing.” Those words hit her like lightning and opened her eyes. “Mmmm, so true.” Actually, this particular politician was rumored to have received bribes and have issues regarding his vested interests. Thus, it was a rather insensitive remark which could be interpreted as “In order to generate something from nothing, one should have no problem receiving money under the table.” However, Shizue interpreted it in her unique manner.

To create something from nothing, one must think for herself, be innovative, and be the first to take action. One also comes up with the means to generate income. Shizue interpreted the quote this way.

A Fire in Ikebukuro Seibu

On August 22,1963, a fire broke out in the seventh-floor Variety Restaurant space of the Ikebukuro Department Store. Hanaya restaurant was also completely burned down.

Later, Arae telephoned Shizue. “Shizue, go to Seiji Tsutsumi’s office now with a bomb and negotiate!” Arae was furious. She asked him what had happened. Apparently, after the fire, there was no contact whatsoever from Hanaya to the Seibu side. The Seibu office, losing patience, gave Hanaya an ultimatum. “If you have no intention to do something, take your store out.”

After Tsuji quit Hanaya, a man named K was put in charge of the store. Arae left everything to K. But K, a former cook, was not the business type. It seemed that after the fire, K was very slow in handling negotiations. Still, according to Arae, there was no way Seibu should resort to such a heartless tactic.

Shizue said promptly, “I see.” She felt the rising competitive nature bubbling up inside. She told Tsuji about it. He said, “Well then, why don’t you talk to Seiji. I can’t go.” Immediately, Shizue headed for the Ikebukuro Seibu.

Arriving at the store, Shizue wasted no time at the reception desk, “I want to see Mr. Seiji Tsutsumi.” The receptionist said, “You have no appointment, ma’am. You cannot see him.” Duly expected to hear the reply, Shizue expressed her surprise in an intentionally loud voice. “Oh, no!” Those around the desk turned their heads.

“I came all the way from my house just because Seiji-san told me to come. And you say he can’t? You must be kidding me!”

Stunned, the receptionist hurriedly let Shizue pass. “Please, please.”

Inside the room for store owners and company executives, Seiji was sitting in the middle with a table on either side. Those who wished to see him were waiting in line at the table. Shizue joined the line.

Slightly surprised at Shizue’s sudden visit, Seiji asked, “What happened?” Shizue explained the situation.

“Here’s what happened. Hanaya was told to withdraw its store because it was too late to contact the Seibu side after the fire. In fact, we were doing our best in dealing with the staff’s future. The Seibu office went too far, don’t you think?”

Then, she pleaded, “To us restaurant people, to close the store we once opened is the greatest humiliation. There is no way we would withdraw our store.”

After hearing that, Seiji quickly introduced a person in charge of restaurant floor. He was known as a capable, shrewd person. He spread a floor plan and pointed to a spot, “If we have another shop, we have only this area available.” The area had the worst conditions, not to mention the fact that its kitchen had to be shared with a Seibu-managed store.

He persisted, “Carpenters have been working already. It’s too late to make change.” Shizue rebutted in an equally insistent manner. “That’s not acceptable.” And pointing to each store with its name on the plan, she clearly declared, “Please move this store to another area. Since it’s Seibu’s direct company store, you can certainly accommodate it.”

Shizue then bluffed, “My father chairs a professional chef association. This case is drawing much attention from members across the nation.” She was high-handed, but she genuinely wanted to avoid closing the store.

As a result, her tactics worked. Hanaya secured the area where Shizue requested, and began to prepare to resume business. Since the area was an ideal place to attract customers, the sales after the reopening recorded a dramatic increase. After this experience, her self confidence in her ability to negotiate grew dramatically.